Date: October 1972

By: Thomas R. Lee

Magazine: ICAO

Page: N/A

By Thomas R. Lee

Member, Board of Directors Wings of Hope (Quebec) Inc. (Canada)

To native Peruvians along the Amazon River, a free flying service provides the means to shorten distances, to assure medical aid and to communicate with the outside world …

While a light floatplane speeds over the Peruvian interior on another of its many mercy flights helping sick or injured natives, a group of Montreal men and women meet over lunch, hear reports and discuss how their air service is doing.

There is never any talk about schedules, or rate structures, salaries or profits, because there are no schedules and the air operation is privately supported and its service is free. Discussion centers on new schemes for raising money to maintain or expand the service, although the question of purchasing a new compass for an aircraft or even a new aeroplane might be considered.

This group is the Board of Directors of Wings of Hope (Quebec) Inc., an inter-faith, non-denominational charity operation. It includes businessmen who are pilots, but also others who are simply interested in the unique humanitarian service that the organization provides.

The Quebec group, now a year old, has only recently assumed complete responsibility for the light plane operation and radio network in the Amazonian jungles of Peru which enable speedy provision of medical, educational, missionary, technical and other services to primitive and remote peoples in that area. The service has turned days, even weeks of travel on foot or by dugout canoe into minutes, and on countless occasions has made the difference between life and death.

Wings of Hope’s free air and radio service to scattered missions and villages in these 185,000 square miles of otherwise barely penetrable jungle was launched a few years ago, with the original organization, Wings of Hope, Inc., St. Louis, supplying and maintaining the aircraft and radio equipment, and a Montreal-based religious order, the Franciscans, financing the operations.

It really had its beginnings in 1964, when a small band of Irish medical missionaries based in an inaccessible area of the Turkana desert in Kenya appealed for aid. Floods, following years of drought, had completely isolated the missionaries and their little hospital from the outside world and from the supplies so urgently needed.

A campaign in the U.S. for funds to provide these people with their own light plane was successful and the famed “flying grandfather,” Max Conrad, personally delivered a Skywagon to them. The aircraft literally saved those medical missionaries from annihilation and opened the eyes of the civilized world to similar needs elsewhere on earth, and to the humanitarian roles that radio and the light plane could play.

Thus Wings of Hope was founded in 1965 by a group of St. Louis, Missouri (U.S.A.), businessmen, some of them pilots themselves or associated with the aviation and related industries: Joseph G. Fabick, who is president today, Dr. John C. Versnel and William D. Edwards.

Its officers and directors, all volunteers, concentrate their efforts on obtaining new and used aircraft, engines, parts, electronic equipment, etc., for their operations which now embrace Africa, New Guinea and South America.

A pilot-priest from Drummondville, Quebec, Father A. Louis Bedard, set the stage for the Wings of Hope involvement in Peru back in 1961. Rev. Bedard was based in Iquitos and was supported by the Franciscan Order in Montreal through its specially-formed group, Missionary Air Transport.

The service lapsed, however, when Bedard departed and a replacement pilot was not available.

In 1966, because of the accidental death of a relative, Jean Laberge, another Montrealer, flew down to Iquitos. There, the need for restoration of such a vital service was impressed on him by Brother William McCarthy, a member of the Marianist Order based in Peru. Laberge’s relative might have lived, it was suggested, had medical attention been provided sooner, something only possible if a light plane were available.

Laberge carried McCarthy’s message back to his brother, Thomas J. McCarthy, Jr., a member of Wings of Hope in St. Louis, who then spearheaded a successful drive for funds to provide in 1968 the first Wings of Hope aircraft in the Amazon. With a brand-new float-equipped Cessna ready to go, all that was needed was a pilot.

Coincidentally, Father Guy Gervais, who had only recently returned from a six-year assignment in New Guinea, learned that a pilot was being sought to take the new Wings of Hope plane down to Peru and to operate it there. The idea appealed to him and with the concurrence of his religious order he went to St. Louis to pick up the new floatplane.

Thus, he resumed in Peru the same kind of mercy flying and ancillary activities he had been doing for so long a time in New Guinea, some 10,000 miles distant.

The flight to South America, however, was not without incident. A few hours out from New Orleans, over the Gulf of Mexico, the plane developed mechanical trouble and Gervais, with his passenger, Brother Tom Duffy, was forced to land. Fortunately, a freighter was in the area and took the aircraft and crew aboard.

Back in New Orleans, Father Gervais switched his aircraft to wheels, arranged for onward shipment of the floats and headed out again for Iquitos, base for the Wings of Hope Peruvian operations.

Gervais’ training from the very beginning was to fit him for such social-medical aid. A graduate of Catholic University, Washington, D.C., he later learned to fly while serving in a hospital there, receiving practical, rudimentary instruction in medicine, studying sociology and anthropology and even learning some dentistry. He also took courses on engines and their maintenance, airframes, and radio maintenance and repair.

With this training and his subsequent experience he has become ready to handle almost any situation, even the birth of a baby in his plane – an event which had occurred on three occasions while jungle flying in New Guinea.

Priest, pilot, paramedic, Father Gervais is conversant in English, French and Spanish, and even a few native dialects. But, as one of his friends says, “His principal communication is with deeds, not words, and the aeroplane is his medium.” To date he has accumulated over 6,000 hours flying over rough terrain, in poor weather and under other conditions that would keep many of us on the ground.

The St. Louis group has now presented the equipment, including a Cessna 205 and a 206, worth some $75,000, to the Quebec group and this small band of dedicated individuals, some 6,300 miles away from the scene of the action, has accepted full responsibility for the entire operation.

“We hope to increase our fleet of aircraft,” says Noel Girard, President of the Quebec group, “and thus make this essential service available to more and more people.”

Operations manager is still Father Gervais, now 40. “He is”, says Mr. Girard, “the personal saviour of hundreds of lives.” Naturally, the opportunities to report personnally to his Board are few, but a radio link with the Franciscan offices in Montreal provides the opportunity for contact with Gervais and his associates on the ground or in the air, whenever the need arises.

Their two Cessna aircraft are based at Iquitos, principal city in the interior and headquarters for the operations, and at Satipo, a community 2,000 feet above sea level surrounded by mountains ranging from 5,000 to 18,000 feet. Some 12 missions or villages are equipped with radio and the eventual hope is to line the entire Amazon basin with good radio communications and air support.

The two pilots, Gervais and Eddy Schertz, are on constant call. “To work in these regions,” says Gervais, “you’ve got to be not only competent but totally dedicated. Here you don’t work for money but for the sheer pleasure and satisfaction of helping people who are forgotten far away in the jungle.”

Flying between 90 and 110 hours a month, Gervais and Schertz each carry some 250 people in that period, including government, educational, medical, and religious personnel; handle some 30 to 35 medical emergencies involving men, women or children, and in addition carry a wide variety of cargo, including mail, medical supplies, food, building materials, etc. Using rivers and their tributaries as landing strips, their aircraft serve as taxis, messenger service, freight carriers and ambulances.

The variety of jobs done by Gervais and Schertz is endless. For example, a director of education is sometimes flown in two hours to a village that would take him two months on foot, the only other means; a missionary who previously required 28 days by boat to reach a village now goes in 45 minutes; a government official wishes to inspect villages in his area, police are needed in another; exploration for oil, minerals or hydro-electric power projects is assisted on the grounds that such development improves the lot of the natives; and the latter are enabled to trade their goods, produce or catch (such as fish) between villages and main market centres.

Where waiting or travelling once took 95 percent of a specialist’s or missionary’s time, Wings of Hope has cut that time to a fraction and has multiplied his usefulness enormously.

Medical emergencies take priority, and Wings of Hope has often spelled the difference between life and death: the villager who cut his foot, the native bitten by a snake, the woman in difficult childbirth, the child stricken with an infectious disease. Not all are saved, but even in death some comfort is provided.

Medical attention is the great need, he says, but with Wings of Hope the battle is being won. An infant mortality rate which was 80 per cent has now dropped to 10.

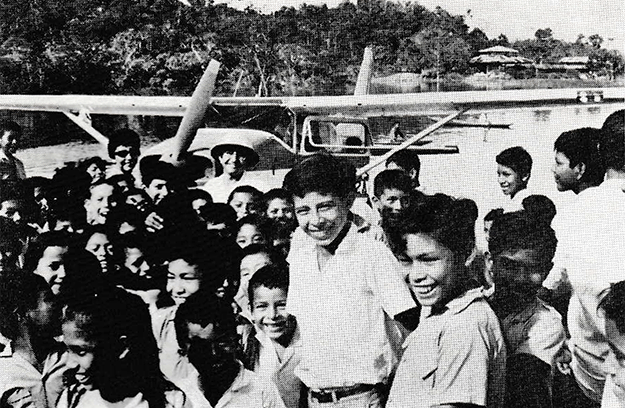

In modern, built-up areas of the civilized world the noise of planes is frequently berated as a curse; in the jungles of Peru the sound of the aeroplane is cause for rejoicing. “To the villagers deep in the jungle,” says Gervais, “the sound of the plane is like being liberated. ‘The pilot is a rriving,’ is the cry, and the whole village – men, women and children – pour out. The sound of the plane to them means life, hope, communication.”

Gervais finds it much more difficult to fly in his native Canada than in the jungle. “Here there is no control tower, no radar, things which frighten me,” he says. “With the compass and my watch, and taking no needless chances, I fly in the valleys and feel very secure. In such a mountainous region, you can’t fly on instruments; when it’s cloudy, you simply have to wait for good weather.”

Being deep in the jungle, he points out, the pilot has to be his own aero-engine, airframe mechanic and radio technician because if he ever has equipment trouble he is strictly on his own.

At the moment, Gervais is building up the Wings of Hope facilities at Satipo. This kind of activity is not new to him either.

When he went on his first bush flying assignment in New Guinea, his first job (with some 300 Papuans) was to hack out of the jungle a 1,500-foot air strip. Hiking back to the coast, he then put together an aeroplane that had arrived in pieces by ocean freighter.

The plane assembled, and with his grand total of 85 hours of flying time, he took off over the 15,000-foot high mountains and into the wild heart of New Guinea.

When the Satipo base is built up, a third plane will be needed, as well as additional pilots.

Needless to say, Wings of Hope has caught the imagination of many sponsors. The U.S. aviation trade press, with the help of two aviation-oriented advertising agencies, has donated time and space to Wings of Hope appeals. Several manufacturers have provided funds, valuable services and even equipment. Pharmaceutical firms have donated drugs and medicines. Others have contributed time and know-how.

And, a magazine publisher recently described Wings of Hope as “the first major non-sectarian aviation-oriented charity ever established.”

Site of lost Lanza found

On 24 December 1971, a Lanza turbo-prop airliner carrying 92 persons from Lima to Pucallpa and Iquitos, Peru, plunged into the jungle and disappeared. The subsequent air search failed to locate the accident scene. Miraculously, on 4 January, 17-yearold Juliane Koepcke, the only survivor, appeared in the town of Tournavista, guided by two Indian woodcutters.

Taking her guides in his Cessna 205, Wings of Hope pilot R.J. Weninger resumed his search for the lost airliner, backtracking the girl’s trail at low altitude. He sighted the barely visible wreckage near Puerto Inca on 5 January, just five minutes’ flying time from where she first met her rescuers on the Seboya River.

CAPTIONS:

#1: This pilot’s view of the Amazon as it snakes its way through the southern Peruvian jungle typifies the difficult region of the Wings of Hope operation. The tepid river is the primary landing strip employed.

#2: The arrival of the Wings of Hope floatplane at any remote village is a time of great excitement, especially for the children.

#3: Twelve villages are now equipped with vital air-ground radio equipment.

#4: Both pilots, Father Gervais and Eddy Schertz (above right), are accomplished mechanics and maintain their own aircrajt.