Date: December 1972

By: Editorial

Magazine: FAA Aviation News

Page: 4-5

When a single-engine airplane, supported by Wings of Hope, solved an American mystery.

In the town of Pucallpa, Peru, near the eastern slope of the rugged Andes, an elaborate shrine stands out against the steamy green-black rain forest. The local people come regularly to fill the many niches of the shrine with fresh flowers . On the very top a white tablet, surrounded by marble angels, bears a map of the immediate area and a pair of gold wings with the legend “Alas de Esperanza” (“Wings of Hope”).

The shrine serves a dual purpose: it commemorates the 52 Pucallpa area residents among the 92 persons who lost their lives in an airplane crash on Christmas eve, 1971, and it pays tribute to the small airplane, operated by a humanitarian group called Wings of Hope, Inc. , which found the wreckage of the crashed airliner in the jungle.

To Bob Weninger, who piloted the Wings of Hope airplane in that fateful search mission, the shrine is a symbol of twelve grueling, anxiety-ridden days of a Christmas season not easily forgotten. It is also a reminder of the importance of a small, single-engine aircraft in remote jungle country.

Aircraft Disappears

On Christmas eve, 1971, a scheduled Lima-Pucallpa-Iquitos flight of a LANSA Electra, with 92 persons aboard, was reported missing in the vicinity of Pucallpa, following a violent thunderstorm.

Bob Weninger learned of the Electra’s disappearance on Christmas day while engaged in one of his normal mercy flights. Because of the demand for his time, December 25 was not a holiday for him; weather the day before had made flying impossible even for a veteran bush pilot, and there were urgent missions waiting, so at a time when people all over the world were sitting down with family and friends for a festive Christmas meal, Weninger was winging over the Peruvian jungles in the Cessna 205.

As he dropped off some much-needed medicine at a small jungle village airstrip and learned about the missing airliner, he immediately radioed the Pucallpa airport to offer his services in the search. Other planes, small and large, converged on the area to help. These included a Peruvian A.F. C-47, and later a U.S.A.F. Hercules, and an Islander flown by noted American aviatrix Jerrie Cobb.

As Weninger joined the others in circling the dense jungles around Pucallpa for the next four days his mood fluctuated. He remembered a C-47 which had been found in Brazil after three weeks down in the jungle with seven survivors, but he also knew that if the Electra had crashed in the mountains the impact and cold nights would make survival after prolonged exposure unlikely.

Weninger was spurred on in his search efforts by the fact that he knew personally some of those missing on the Electra. The LANSA copilot was his friend, Jerry Villegas, who, although not scheduled for the flight, had agreed at the last minute to substitute for another pilot. Villegas’ wife and two-year-old son were among those who waited anxiously for word of the missing plane.

Rumors of where the Electra’s engines had last been heard were numerous, but there were no really solid clues to go on, so after four days of searching the Pucallpa area Weninger decided to return to Satipo and his neglected mercy flights. He felt that he could combine his regular work with the search, since the airliner was scheduled to pass over many of his regular ports of call.

Hope faded as ten days dragged by with no word or sign of the LANSA airliner, but on January 4th Weninger’s little red and white Cessna landed at Pucallpa to find great excitement in the town. There were reports that a survivor of the aircraft crash, a girl, had been found by woodcutters near Tournevista, a small village only a few miles from Pucallpa as the crow flies but many times that distance by river. The 17-year-old German girl, Juliane Koepke, had made her way alone through the jungle for nine days by walking, stumbling, crawling, swimming, and finally floating down the river on a crude handmade raft. After she had been found, semiconscious and half-starved, it had taken the woodsmen two more days by boat to get her to the town and medical aid.

Juliane remembered little of the crash except flying through space after seeing a fiery engine, later regaining consciousness and starting for help, pausing only to pick up a Christmas cake she had been taking to her father in Pucallpa. The girl had been trained in jungle survival by her parents, noted ornithologists, and with her mother (now missing) was returning to their home in Pucallpa after Juliane’s graduation in Lima.

Weninger immediately took off for Tournevista in the Cessna, as did Jerrie Cobb, who was to fly the exhausted girl to Pucallpa and her waiting father.

The aerial search was intensified, spurred on by Juliane’s report that several other passengers had survived the crash. Weninger delayed his takeoff in order to talk to the Peruvians who had found the girl. In spite of their great fear of airplanes, he persuaded them to fly with him in his search and point out the location of their camp. They told him the girl had walked about a kilometer a day, then followed a spring and the river.

Once airborne, Weninger backtracked over what he felt the path of the girl had been radioing his course to other search planes. As the larger military aircraft followed the river from a higher altitude, the Cessna barely skimmed the treetops. Suddenly a flash of metal caught Weninger’s eye; he circled frantically to find it again, a crumpled piece of fuselage lodged in limbs high above the ground, almost completely concealed by the 130-foot treetops. Weninger announced his find over the radio, and the pilot of the Hercules, circling above, radioed back, “How the hell did you ever find it? We can’t see anything.”

There was no sign of life.

After directing the other planes and ground parties to the wreckage Weninger flew sadly back to Satipo. After landing he made a simple entry in his flight log:

“January 5, Puerto Inca LOCAL (Search and Rescue, LANSA) Tournavista, Pucallpa.”

That he had found the long-sought airliner was not mentioned. It was all in a day’s work for mercy pilot Robert Weninger and his Wings of Hope airplane.

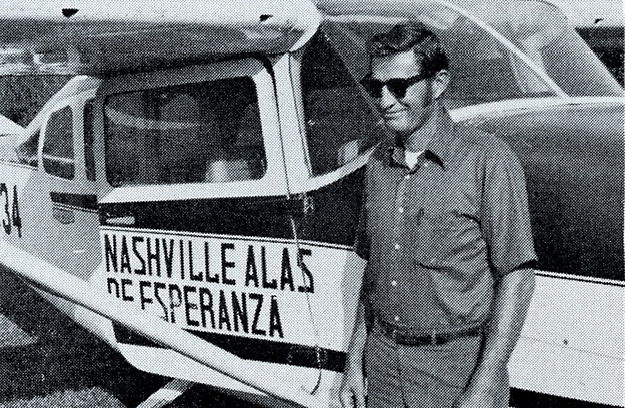

Bob Weninger is only one of many humanitarian pilots flying small aircraft in remote and rugged corners of the globe. Weninger’s plane, a 1963 Cessna 205 Skywagon, was supplied and supported by Wings of Hope, Inc., an American-based, aviation-oriented charity whose primary purpose is to relieve human misery with the aid of small aircraft.

Headquartered in St. Louis, Wings of Hope is staffed primarily by non-paid volunteers, mostly businessmen. More than 90 per cent of all donated funds go to the purchase and support of airplanes (the “fleet” now numbers about 20 aircraft, based in South and Central America, New Guinea and Africa). Within the limit of available funds, the organization offers its services to any legitimate humanitarian enterprise regardless of affiliation. No one can hire or charter Wings of Hope aircraft. Every service is gratis and no government involvement is sought, but wherever these planes operate they bring friendship to America and appreciation for general aviation.

This unusual organization began in St. Louis in 1964 when a group of professionals and businessmen first became aware of the tremendous need of a small group of Irish medical missionaries based in an almost inaccessible area in Kenya, East Africa. Earlier the mission had been given a Super Cub, which was flown by one of the nuns, but it was frequently inoperable because the hyenas insisted on eating the fabric covering during the night. In 1965 long-distance pilot Max Conrad delivered the first metal airplane, a donated Cessna Skywagon, to Kenya.

Later the St. Louis group expanded and incorporated as Wings of Hope. Affiliates were formed in other countries, and planes purchased for other locations. Individuals and corporations occasionally contribute surplus aircraft and parts which are either repaired for use or sold to buy other planes or parts. From remote corners of the earth come dramatic reports of lives being saved, suffering eased:

A Peruvian Indian bitten by a deadly bushmaster snake is flown to a well-staffed hospital; the hour’s flight would have taken many days by boat.

A woman near death from childbirth complications is flown from the mountains of New Guinea to a seashore village hospital and her life is saved.

A critically burned boy in Kenya is transported to modern medical facilities.

New Guinea villagers are trained in health education by a missionary group flown in regularly.

Medical missionaries compress what once was a year’s grueling jungle travel into two or three weeks of life-saving itinerant treatment.

Because this type of flying is done under the most demanding of circumstances, special training and precautions are needed in aircraft maintenance and flight operations. Putting the right people in the right airplane for the job at hand is not easy. Missionary flying over isolated jungles has no room for improperly trained, undisciplined pilots, regardless of their deep religious or humanitarian dedication. Pilots are not accepted by Wings of Hope unless they have wide experience, preferably in the bush, and are also airplane mechanics; and they are given specialized training in the field.

Wings of Hope field director in South America is Padre Guy Gervais, a French Canadian pilot and paramedic as well as priest and A & P mechanic. “Padre Guy” flew for six years in New Guinea before going to Peru, and while he was learning to fly he also took time to learn to pull teeth – a talent which comes in handy in back jungle areas where the natives never see a doctor or dentist and tooth decay is rampant. He has flown some 9,000 hours in 12 years in the jungle without serious incident, and now in addition to the flights he makes in the float-equipped Cessna he also gives other pilots specialized jungle flight training.

Floating “Airports”

Since in many jungle areas “the river is our airfield,” pilots get training in float plane takeoffs and landings and in river pilotage. A current of 15 miles an hour in a twisting, snake-infested river over-hung with dense foliage makes taxiing and mooring tricky. Before he stops the engine, the pilot must have mooring line in hand, ready to step down, hook the floats and jump on the bank in almost a single motion. Padre Guy’s efforts to teach natives to help has met with limited success: many are afraid to get close to the airplane. Occasionally planes end up tangled in the thick tree limbs, or beached on a rocky shore.

Fuel and oil must be carefully watched for correct type, and for cleanliness. Both are stored in 50-gallon drums and the pilot must personally oversee servicing every time; overeager helpers could easily pour oil in the gas tanks and vice versa. Fuel is strained through a chamois and checked for color and grade; oil is inspected to be sure it has not been confused with diesel fuel or non-engine lubricants.

Bush pilots learn and respect the runways they must use. Padre Guy has made thousands of landings without incident on runways less than 1,000 feet long, more or less level. Some airstrips double as cow pastures, and at night errant cattle are apt to lick the paint off airplanes, scratch their backs on the elevators, or file their horns on the prop and fuselage. The jungle preflight inspection has to be unusually thorough.

Humidity is the great enemy of the airplane in the jungle. Operators have to be constantly on guard against corrosion, against mildew, against moisture in the fuel and in the air. Rainstorms are frequent but usually of brief duration; the pilot learns to set down on the nearest stream, wait them out, and continue on his· way. VFR is the order of the day; there are virtually no NAVAIDS, only scattered radio ground stations, and no repair stations. The pilot with mechanical trouble makes his own repairs on the spot, or he has a long wait for parts or transport. To qualify in a “jungle-hopper” you have to acquire an independence of action virtually unknown to most pilots of today. Your airplane may be inscribed with Wings of Hope, but if you wish to fly safely in the tropical bush you had better assume, like Padre Guy, that Providence is on the side of the cautious and the competent.

CAPTION:

The Amazon River is a frequent landing field for Peru-based Wings of Hope floatplanes. Many lives have been saved by mercy flights to remote villages where the only other transportation is a dugout canoe or mule cart. Above-map on the flower-filled shrine at Pucallpa pinpoints the spot where Bob Weninger and his jungle-hopper found the wreckage of the LANSA Electra.