Date: May 1975

By: Stuart Nixon

Magazine: Air Line Pilot

Page: N/A

Somewhere in the scorching wastes of Kenya’s Turkhana Desert are the bones of an airplane that once brought life to thousands of people. In a very real sense it is still flying today with its cargo of human hope.

The first time the Piper Super Cub touched down on African soil, it was riding in a crate inside an Air Force C-130. Date: March 23, 1963. Place: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Waiting for the Cub at the Addis airport was Bud Donovan, an ALPA pilot who was then 27 years old and whose normal habitat was the chilly corridor between Seattle and Anchorage where he rode in the right seat for Pacific Northern Airlines (now merged with Western Air Lines). The sequence of events that put Donovan in Ethiopia on that particular day was until now an untold story of courage, generosity and personal commitment. Sharing the central role was another ALPA member, Donovan’s partner in tne left seat, 42-year-old Jerry Fay.

Thanks in part to their efforts, an unusual humanitarian program called Wings of Hope is now a successful operation dispatching aircraft and pilots to remote sites around the world where the unique services of aviation can often mean the difference between life and death.

Fay and Donovan did not go out looking for halos. In 1962, Fay met a Catholic nun who told him about Bishop Joseph Houlihan, a missionary in Kenya, who was seeking an airplane to help ferry medicine, food and other supplies into the Turkhana Desert for victims of a 1961 famine that had wiped out thousands of nomadic tribesmen and was threatening many more. Bishop Houlihan had set up emergency relief camps, staffed by nuns and priests, including a camp at an old British fort named Lodewar and another about 25 miles away at Lorogumo.

Food donated by the United States was trucked in over roads that were patchworks of holes, rocks and shifting sand. The main road, running some 175 miles from Kitale to Lodewar, took from seven hours to seven days to negotiate, depending on the season. An airplane could make the trip in an hour.

Fay talked with his copilot, Donovan, and suggested they join forces to help the missionaries.

“I tried to make it a committee effort,” Fay recalls. “At that time I was an ALPA council chairman .. . and was imbued with a committee sense of doing things.”

The two men picked the Super Cub because it could be rigged with large tires and could land in 400 feet or less. A Piper agency in Tacoma, Wash., owned by the brother of a PNA pilot, offered to sell one at cost and to throw in extra avionics and tires. Fay ended up paying most of the $10,500 price tag out of his own pocket when a donation appeal failed to generate much cash.

To get the Cub to Africa, Donovan explored various alternatives. He finally negotiated a deal with the Navy to haul it from Norfolk to Naples, Italy, where the Air Force would pick it up and fly it to Addis Ababa. While Donovan was working this out, Bishop Houlihan made a trip to the U.S. to raise money for his famine-relief campaign. During a stopover in St. Louis, he looked up Bill Edwards, who was referred to him by a mutual friend. When Edwards asked if Houlihan needed anything besides money, the bishop mentioned the Super Cub and said a larger plane could provide additional support to carry personnel the two-place Cub couldn’t handle.

Edwards discussed the idea with a friend and private pilot, Joe Fabick, president of Fabick Tractor Co., who agreed to help Edwards establish the Turkhana Desert Fund. Although they didn’t suspect it at the time, it was a venture that would lead to much bigger things.

In February 1963, Donovan headed to Naples to await the Cub, followed a week later by Fay. When the Cuban missile crisis delayed the ship, Fay went to Germany to firm up arrangements with the Air Force, and Donovan flew to Addis to check out facilities for uncrating and assembling the plane. Momentary trouble developed when the Ethiopians proposed to levy a transit tax on the Cub, but Fay “took the bite off” through a pilot he met en route to Addis, who happened to be a golf partner of a local finance minister.

Pending arrival of the Cub in Addis, Fay and Donovan took off for Nairobi, where they were met at the airport by Bishop Houlihan. While Donovan ran errands in Nairobi, Fay made the long trek to Turkhana to meet the missionaries and make a survey of landing sites.

“I was there for about a week,” he recalls. “I carved out a little airstrip, which wasn’t much of a project. But there was no hangar, no facilities, no gas, not a damn thing. The enormity of this project hit me, because these people didn’t even know that you landed an airplane into the wind. It was starting from basic scratch.”

As for Turkhana itself, that was another shock. “It was nothingness,” says Fay. “I’ve never seen such a bloody mess in my life.”

In Nairobi, Fay picked up Donovan and headed back to Addis, where they discovered the Air Force had decided not to release the Cub, figuring the telegram Fay had sent requesting it was a ploy by the Ethiopians to impound the plane. Fay was forced to return to Germany to resolve the problem. During this time the effects of living out of a suitcase and jumping through time zones finally caught up with him. Tired and ill, he had to return home.

The Cub showed up in Addis on Saturday, March 23. Donovan remembers : “I had to wait until Monday to get started on it. But I had it together by Wednesday night. Thursday I took it up for the first time to check on fuel consumption and performance.”

The test flight was a short hop south of Addis to Lake Awassa. At the lake, Donovan put the Cub down on a deserted stretch of ground, knocking off a wheel. Since the Cub’s radio crystals weren’t suitable for Ethiopia’s aviation frequencies, he couldn’t advise Addis of his location. He carried the wheel some nine miles to a game preserve where Ethiopian Airlines maintained a radio shack. When he got there, the operator was off duty.

“As I walked out of the shack to go fix the tire,” Donovan recounts , “a DC-3 flew over the camp looking for me. About 20 minutes later, the guy came back to the shack, and we got hold of Addis and told them everything was all right. But it was too late. By then, the Ethiopians were mad.”

They were angry because a few weeks before Donovan got to Ethiopia (as he later found out), a crop duster had been forced down in a remote section of bush country, and the pilot was eventually discovered tied to a tree with his stomach cut open.

Unaware of this, Donovan flew back to Addis the following day, where armed soldiers were waitingfor him at the airport. Hustled into an office and reprimanded by the Ethiopian counterpart of the FAA, he was ushered to the doorway and advised to make Ethiopia the last item on his list of future places to visit.

“That is exactly what I did,” Donovan says. “I walked out the door, went straight to the airplane, started the engine and got out of there. A friend had to get my clothes from the hotel and bring them to me in Nairobi a couple of days later.”

Donovan arrived in Nairobi late that night, putting 700 miles between himself and Addis Ababa. The next morning, the U.S. consulate handed him a bill from the Ethiopians for $100,000, the alleged cost of the search and rescue mission at Lake Awassa.

“I couldn’t pay it,” Donovan quips. “I didn’t have my Diners Club card with me.”

On the other side of the Atlantic, in Massachusetts, the U.S. branch of the Kenya nuns’ religious order had selected one of its members to go to Turkhana to fly the Cub. She was a 33-year-old nurse from Worcester, Sister Michael Therese, named after the patron saint of pilots . Once she assumed her duties in the desert, the Turkhana tribesmen would give her another name: Sister Ndege – “big bird.”

In June 1963, after Donovan had returned home from Kenya, Sister Michael Therese went to Seattle to thank the two PNA pilots for their gift ofthe Super Cub, which was parked in the Turkhana sun waiting her arrival three months later. Ahead of her lay five years in which she would ferry the plane to Kitale, Lodewar, Nairobi and other sites, adding hundreds of hours to the 34 she brought with her when she first set foot at Lorogumo. Before she was finished, her hands would be discolored from the melting plastic of the Cub’s control stick.

While Sister Michael Therese was getting ready to go to Africa, Bill Edwards in St. Louis was struggling to move the Turkhana Desert Fund off dead center. In the summer of 1963, he and Fabick enlisted the help of Paul Rogers , vice president of Ozark Air Lines, who in turn introduced them to George Haddaway, publisher of Flight magazine. Haddaway got in touch with an old friend in Cleveland, Dwight Joyce, the late board chairman of Glidden Co. and a strong backer of general aviation. Joyce generated a memorandum about Turkhana to 30 or 40 business associates.

“In the next seven weeks,” Edwards says, “we received, in round numbers, $1,000 a week – essentially the balance we needed to buy the airplane.”

Edwards had chosen a Cessna 206 Skywagon, a six-place, $30,000 aircraft with metal skin. The metal was important because when Donovan returned to Kenya in the winter of 1964 to work with Sister Michael Therese, he discovered that the Cub’s fabric shell was being eaten by hyenas.

News of the flying nun in her battered little Cub soon brought a chain of requests for Fay and Donovan to help start similar projects in other parts of the world.

“We weren’t set up to handle these queries,” Fay says, “so we referred them to Edwards.”

Edwards wasn’t ready for them either. The Turkhana Desert Fund was supposed to be a one-shot effort. But the experience was there, and so was the interest. Edwards and Fabick went back to the friends who had helped them before and put together a new concept: a nonprofit organization to develop aviation programs for special human needs.

Wings of Hope.

Today the St. Louis group operates a worldwide system supported entirely by donations and volunteer services. “We concentrate essentially on medical needs, mainly emergency,” explains Edwards, “and on support of development projects, helping people to become self-sufficient through sound, well-conceived programs – particularly ones plugged into aid and assistance from other international groups like Red Cross, Oxford Famine Relief, Canadian Hunger Foundation, etc.”

Many charitable and educational organizations need aircraft support in the field, says Edwards, but few can afford it or know where to find it. With eight years of practical know-how already logged, plus the two-and-a-half years spent in acquiring the Skywagon, Wings of Hope can offer this service. Thus far it has placed or assisted with some 30 airplanes in Africa, South America, Australasia and other locations, not to mention personnel, equipment, supplies and technical support. Currently on order, with delivery expected this month, is another Cessna 206 to replace the one in Kenya, which is needed for duty at another site.

Most important right now, Edwards reports, is the need for active participation from pilots – not money, but personal participation. Help is required in communications, training, maintenance and flight operations. All it takes is some spare time and a desire to get involved in something a little different for a humanitarian cause.

The results can be startling. Fay recalls how people first reacted when he and Donovan were trying to get the Super Cub to Africa: “When we’d start spelling out what our project was, they’d look at us with total disbelief. Apparently they weren’t used to the idea of somebody doing something for nothing for somebody else. But once you got the thing across to them, they became so cooperative, you

wouldn’t believe it.”

This is the spirit Wings of Hope is trying to generate. As Fay comments: ” The American-built light plane is still a magnificent unifier of people, and the little ships are still the required unit for medical aid in many parts of the world.”

Edwards adds: “In a fundamental way, a couple of ALPA guys helped get this whole thing started . We’d like to invite every ALPA pilot to join us in building on what Jerry and Bud worked so hard to make a reality.”

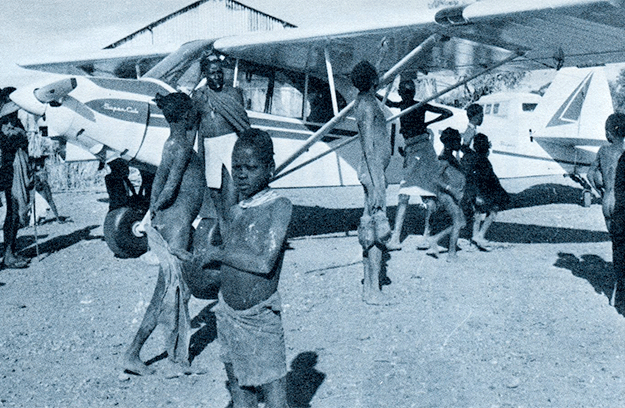

CAPTIONS:

#1: Far-left: Riding desert air currents is Super Cub donated by two ALPA pilots to help starving nomads in Kenya. Left: Cub’s first pilot, Sister Michael Therese, welcomes fellow pilot Max Conrad to African airstrip.

#2: Good roads in Kenya stop at Kitale, supply point for desert relief camps set up in 1961 to aid famine victims. Super Cub ferried provisions from Kitale to camps.

#3: Left: ALPA’s Bud Donovan shows movie camera to Kenyan children while visiting relief camp at Lorogumo to help deliver Super Cub to missionaries. Camp consisted of a few tin shacks and native huts. Above: The airplane sat in the sun, where it eventually was chewed on by animals.