Date: February 1971

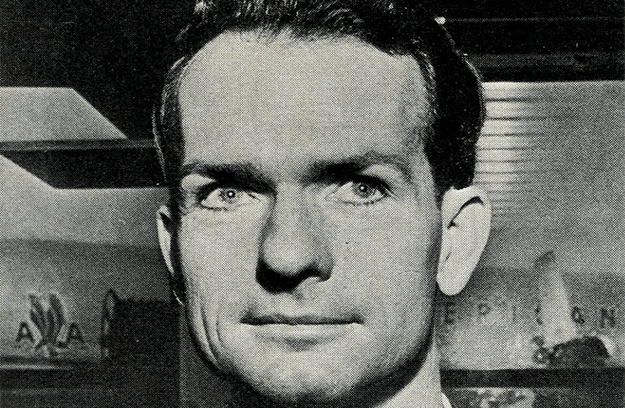

By: Thomas A. Dooley

Magazine: Flight Magazine

Page: 26-27

This article on Medico is as current today as it was in April, 1958, when it appeared in the New York Times magazine section. It is reprinted in part with permission of the New York Times

There is a general belief that foreign aid is the job of the Government alone. But in actual fact, no Government can ever replace the individual, his self-reliance, his initiative, his sense of self-responsibility. No dollars-to-person program can ever replace a person-to-person program. No dollars-to-person program can ever inject the warmth, compassion, and spontaneity that characterize the American way of life. Besides, America is based upon the concept that ordinary men can accomplish extraordinary things.

For several years I have run a small village hospital on stilts. Our hospital is on the China border in the northernmost village of the Kingdom of Laos. The men who work with me are superb men. Three of them were former Navy corpsmen who worked with me in Vietnam during the anguish of the refugee evacuation of 1954 and 1955. Two other men were students at the University of Notre Dame. These men know how to deal with the primitive people of our village, not as they ought to be, but as they are.

From the experience my men and I had as a result of our Navy duty in Indochina in 1954-55, we learned the importance of each man doing what he can. We learned that it was our individual responsibility to aid those in the world who “ain’t got it so good.” We formed a medical mission to accomplish what we could. Perhaps it was paltry in terms of dollars. But we believe that it is better to light one candle than to curse the darkness.

In 1956, at the invitation of the Royal Kingdom of Laos, we went to the northernmost tip of that nation, an area where white men had rarely been seen. We built a hut of a hospital. We had no electricity, no running water, no electronic physiotherapy paraphernalia. But we did have the most important qualification for a hospital – compassion.

In that simple experience, plus our experience in Vietnam, we have seen the value of medicine, and the power of kindness. And we have seen the awesome need! Our experience has proved to us that a heart-to-heart, person-to-person program, however simple, can be extremely powerful, efficacious and appreciated.

Our experience has shown, too, that it is wrong to stand on a pedestal and attempt to reach down and mold the Asian to a mirror image of the American. We have seen that it is much better (though sometimes more messy) to get off that pedestal, stand knee-deep in the stench of some parts of Asia, and attempt to urge and lift the Asian up a bit – gently, slowly, steadily, but surely.

The pitfalls of foreign aid are many – in the hands of Government or in the hands of the individual. One of the most malicious dangers is the attitude, “Why help them? They don’t want to progress, they are content the way they are. . . . Anyway, they can never handle the job without us.” The effects of this haughty, supercilious attitude can be devastating. The recent history of colonialism has proved that.

Another attitude frequently adopted by those who aid foreign nations is that no other nation, no other culture, no other civilization than their own has anything to offer the world that is worth while. This “white-man-ism” is historically untrue.

In dealing with people less advanced than we, let us also remember that this is human intercourse. This is a human picture. We must remember that men and women are of flesh and hue, heart and soul, as well as simply people who need penicillin, electricity and plumbing. In each Asian there are strong undercurrents – “face,” pride, ambition, the yearning for betterment. If the aider plunges into the stream oblivious of them, he may be swept away.

As even the poorest peasant has his pride, we established the rule that every peasant treated in our hospital had to pay for our services according to his means. We had a large basket just inside the clinic entrance. Every day it was covered with eggs, fruit, vegetables, scrawny chickens, and sometimes a couple of bottles of moonshine (which burned beautifully in our spirit lamps).

So it comes about that everything we cast upon the waters in Asia will return to us a thousandfold. If we cast nothing, we well may lose all.

The earth has shrunk too much to permit Americans to live in a mansion in the midst of world slums. Two-thirds of the human race, to whom adequate care is inaccessible, are sick and hungry. There are vast millions of souls who have never seen a doctor. There are people who are born, suffer, live, suffer and die without the simplest medicine. Many of these people are becoming convinced that their plight is not inevitable.

Here it becomes obvious that medicine has a most powerful effect on the recipient. And it is appallingly obvious that the United States is not utilizing therapeutic medicine :is an instrument of our foreign policy. By failing to do this we are missing an important opportunity, with perhaps a dreadful consequence. The sick and hungry of the world can give impetus to the unrest that is of ten the prelude to revolution.

In the field of foreign aid, medicine has a unique role. It has a role in human destiny, far above the give and take of national rivalries. It rises above the fears of colonialism or of domination by selfish foreign interests. At the same time, medicine affords American doctors an opportunity for service to all mankind while serving their own nation.

Now the cynic says: “All right, it should be done. Along with Government dollars, libraries, guns and tanks, let’s send individual doctors, nurses, aides and pills. But you’ll never find enough of any of the four.”

Another reaction always brought forth by the suggestion of a medical-aid program on a nongovernment, nonsectarian level is: “How much will that kind of program cost?” From personal experience, I have the statistics. With contributed medicines and cooperation from the host Government, we built, stocked, supplied and ran a hospital treating about 100 out-patients a day and hospitalizing thirty patients. Included was a teaching program and plenty of major surgery. The cost of this per month was less than ‘that of a low-price 1958 automobile.

And to stagger the cynic, here are the statistics on the response from the “capitalistic companies” and the hearts of America. From five pharmaceutical houses alone we have been given enough of the basic pharmaceuticals to run six small hospitals in the field for two years. From one surgical supply house we have been given the basic instruments for six operating rooms. We also have six medical libraries, and tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of other medicines and instruments from individual donors.

It has long been realized that foreign aid is essential to the life of other nations. And their life is essential to ours. Lately the unique role of therapeutic medicine, on a Government or private scale, has become more obvious. Simple, tender, loving care, even the crudest kind of medicine, inexpertly practiced by the most ordinary doctors, can change a people’s fear and hatred into friendship and understanding. The majesty of medicine can reach into the hearts and souls of a nation. It can translate the brotherhood of man into a reality that plain people can understand.