Date: January 26, 1983

Location: Clayton, MO

By: Joan Rice

Newspaper: Clayton Citizen

Page: N/A

Every time he picks up the phone to make a call or dictates a letter to his part-time secretary from his Hampton Ave. office, Clayton resident William Edwards begins the motion of a large gear, the cogs of which turn a seemingly endless supply of other smaller gears, which in turn work with foreign gears from both charitable and business machinery across the world.

In the remotest areas, the most isolated villages of the world, need still exists. People have learned to turn to Edwards and his non-sectarian organization, Wings of Hope, for equipment, supplies, emergency missions and connections.

Wings of Hope volunteer pilots who flew in countries such as Guatemala, New Guinea, Canada, Brazil, Honduras, Peru, Alaska, Paraguay, New Mexico and Kenya can relate a multitude of interesting stories of their experiences among people whose foremost technology still depends on the plow or herds of sheep, pigs, goats and other livestock.

Perhaps, the only story that tops these is that which explains how Wings of Hope came into existence. According to Edwards, he didn’t just decide to start a charitable organization, but it evolved out of constant need which was not being fulfilled by any other organization in the world.

In the process of meeting these needs, Edwards was increasingly drawn into a web which ultimately and formally came to be known as Wings of Hope. It is the only non-sectarian, non-profit, non-political “humanitarian” aviation agency in existence.

Obviously, the agency means a variety of things to many different people. But in the beginning, when no thought was given to formally organizing, the efforts of Edwards and others working with him meant a source of support to Irish and American medical missionaries working in Kenya.

They sought out the St. Louis businessman back in 1962. Apparently, the Kenya missionaries had been using “a small, inadequate airplane to ferry medical supplies, food or famine relief and medical personnel to needy areas,” states the agency’s prospectus, a statement outlining the main features of the business enterprise.

“Kenyan Bishop Joseph Houlihan came to the United States in the late summer of 1962, and he was directed to my wife and me for support,” Edwards began thoughtfully. The Clayton couple held a party in their home shortly thereafter, inviting a few of their friends and business associates. “Out of that meeting came the Wings of Hope,” says Edwards, speaking summarily.

It seems that Bishop Houlihan’s Kenyan diocese included Turkana Desert where a famine had dealt hard blows to nomads who inhabited the African wasteland. The missionary explained that money was needed, although other help would not be refused.

The United States government had already committed a good quantity of food to the cause, but this could only be delivered as far as the town of Kitale, 175 miles from its destination. There were no roads beyond that town.

Oh, but a plane could do all this, and more. Medicine could be transported as well as seed grains to make the tribes self-sufficient again. Critically-injured people could be flown to city hospitals. There was just no end to the uses Father Houlihan had devised for an aircraft.

Without money to buy an airplane outright; Edwards, a manufacturer’s agent, did something better, that which every enterprising businessman does when he wants something that is out of his immediate reach — he made a telephone call. It’s recipient was a prominent St. Louis businessman and friend, Joseph G. Fabick, a top official of the John Fabick Tractor Co. and just as importantly, a private pilot.

The action generated by this telephone call is a classic example of “the ripple effect.” Fabick was interested and decided to contact Paul J. Rodgers, senior vice president of Ozark Airlines. Rodgers thought their interests would best be served by getting in touch with George E. Haddaway, publisher of Flight Magazine.

The core group of four men was all it took. They decided to solicit pieces of used equipment in the magazine, Fabick would have it repaired. This in turn would be sold and the proceeds would be put toward the purchase of the plane.

Three years after the initial inquiries were made, a pilot delivered the multi-purpose airplane, a Cessna 206 to Father Houlihan in the Turkana. That one flight caused yet another ripple, only this time it was among other humanitarian groups working in similarly underdeveloped regions , of Paraguay, Brazil and Alaska.

“We more or less Just started in the typical see-a-need-and-help-meet-the-need way, and found that with each need we met, the ripples came back with more requests,” remarks the thoughtful, methodical

Edwards.

Edwards observes that a number of people from his church, Immacolata Parish, 8900 Clayton Road, provided “a strong contingent of early support.” Among them Fabick were the late Thomas J. McCarthy, Paul J. Rodgers, John T. Tucker, D. Robert Werner, David Flavan, Mill Walston, Joseph Desloge Jr., James 0. Holton, Oliver L. Parks and David Kratz.

A former Clayton citizen, the late Dr. John Versnel was involved in Wings of Hope’s Peruvian endeavors, Edwards notes. He adds that even former Clayton Mayor William Hedley actually flew with his wife over the Amazon during a Wings of Hope mission.

Now, Wings of Hope has its hands full.

After its first groping to supply humanitarian groups throughout the world with airplanes, pilots, mechanics, technical advice and equipment, the aviation agency sought to “get as many specialized airplanes airborne as soon as possible to service personnel in the field.” The agency sought donations of money, equipment, time and talent from the various components of the aviation community. Over the course of time, contributions of every sort flowed into the agency’s office.

“We have assisted a variety of humanitarian programs in some important way on five continents,” Edwards says with satisfaction. He adds that his business has been an active participant in helping various service organizations get at least 50 aircraft in the field.

“About a half dozen of them are in the Wings of Hope name now, but there are more than two or three times that number in the field” with which the agency deals directly, the staid man conjectures.

“We do less owning and operating than consulting in special field services,” he explains. As a matter of fact, former airline pilots who volunteer to fly for Wings of Hope usually make contacts of their own in the field, and eventually join charitable organizations as a result, he says.

“The people we recruit become employees of service organizations in the areas where they work. That makes us a little unique. We’re not an employer as such. We bring together the need and the volunteer to help meet that need,” Edwards generalizes.

“We’re basically an enabling catalytic group.”

The company’s practice of continually soliciting in various aviation trade publications not only afforded it used airplanes and specialized equipment, but manpower as well. This was how Wings of Hope’s Operations Director Roy Johnsen became involved, though it was a while before he actually acted on his thoughts.

“I’ve always been a service-oriented person,” remarks Johnsen, whose aviation career included assisting a mission group in Arizona by flying Navajo patients to area hospitals.

Johnsen’s contact with that group was Father Ray McKee, a man who had been on the advisory board of Wings of Hope since its inception. Father McKee suggested that Johnsen go to work for Wings of Hope. For a long time, Johnsen gave it little thought.

Eventually, in 1975, Johnsen took a job as a general aviation operations inspector for the Federal Aviation Administration.

He had stayed in touch with Wings of Hope, however.

In 1978, during a conversation with Father McKee, Johnsen notes that he asked the priest “half in jest” whether “Wings of Hope had a seat for me someplace.”

Father McKee replied that “there was an urgent need for a pilot in Honduras,” according to the tall aviator. That response triggered a curiosity within Johnsen that would only be satisfied by first-hand experience. He arranged for a leave of absence from the F.A.A. without pay and spent a year in Honduras, from July of 1978 to July of 1979.

He operated the two aircraft on which the organization had come to rely, the Cessna 185 and a different model, the 206. He flew in settlers of the Honduran jungle country and “moved out medical emergencies,” he explains.

The operation began in 1977, he reports, and continued for one and one-half years after Johnsen returned to his job with the F.A.A. Within four to five years, the population growth in Honduras’ jungle regions lept from 5,000 to 40,000 and “the low subsistence level population became economically viable,” he says.

The “acceleration factor” in growth was due to use of airplanes, facilitating faster transportation under such conditions by a ratio of 20 to one, he emphasizes. He gave an example of a woman who, in the process of childbirth, runs into complications. “Without an airplane, she’ll be doomed to die,” says Johnsen.

Furthermore, “any kind of accident that can happen in the wild happened out there.”

With the assistance of the Ministry of Health and nurses from the Peace Corp., Wings of Hope transported medical supplies into the jungle region of Honduras, decreasing the infant mortality rate among the natives from 80 to 30 percent. “Intensive mid-wifing” courses held in the jungle did the trick.

Not only is medical service enhanced by airplane transportation, but agricultural efforts are as well, he notes. He, as a Wings of Hope pilot, proved to be the “vital link” between jungle fields and city markets, where crops were sold.

Whereas once crops were taken overland by mule, the Wings of Hope aircraft made the trip much more economically. The reasons given by Johnsen seemed almost infinite in number, two of which were that crops stood excellent chances of being infested with insects and contaminated with water during the overland trip.

“Between 1978 and 1979, we flew out their (the Hondurans’) entire corn and rice crop,” states Johnsen. This entailed transporting as much as 200,000 pounds in one month, he adds. Indeed, “we have flown as much as 12,000 pounds in one day,” he comments.

The motivation for a man to serve other less fortunate than himself is deep-rooted, according to the aviator. It arises out of “a deep soul awareness of God in faith,” he says placidly.

“They don’t need world-savers, but people who truly do want to give of themselves. And it’s amazing what those people can do.”

Wings of Hope is designed to be a versatile service agency, and in this respect, Johnsen maintains, it is unique. “We can respond to a wider variety of needs because the number one objective is humanitarian service.”

Use of aircraft “merely enables the accomplishment of things that cannot or would not be accomplished without time involvement,” said the man who has 35 years of flying experience. “When other lines of communication exist, use of the airplane as a tool is not of prime value. It cannot compete with established surface transportation.”

Once Wings of Hope has accomplished its goal in a region, the pilot moves on to another remote area in need of similar assistance. “Our goal is to get the people to help themselves to a point where they no longer need help” from the aviation agency, says the firm’s operations director.

Presently, Wings of Hope has become so respected among sectarian missionaries and other charitable groups that its word of approval is highly valued.

Last week, Roy Johnsen met a third world vehicle designer for observance of the vehicle’s versatility in use. The meeting took place on a bitterly cold day at the airstrip of Weiss Airport in Fenton. There, Earl Miner of Marshfield, Mo., had hauled his invention, the Little International Vehicle (LIV) for scrutiny.

Miner, an industrial engineer, had spent some of his life as an aeronautics engineer designing defense weapons. He became disgusted with this particular use of his expertise and decided that “it was about time that someone used technology for peace.” To this end, he began working for the Office of Creative Ministries of the United Methodist Church.

Miner was commissioned to develop a vehicle of “a universal design to be manufactured worldwide using standardized components and assembly procedures with minimum tools and capital investment.”

The result of 15 years of work was LIV, a vehicle that can perform tasks from hauling small livestock to produce to transporting an injured man to a medical base. Weiss Airport is the airfield from which most of Wings of Hope’s operations are carried out. A number of people, including pilots, board members and administrators from Wings of Hope, were on hand to observe the demonstration of the remarkable invention last Wednesday.

Johnsen remarked that Wings of Hope takes interest in such vehicles because they offer “a parallel interest to that of aviation,” and designers such as Earl Miner turn to the non-sectarian agency for endorsement of their products.

Clarence “Clancy” Hess, a retired American Airlines pilot whose connections with the St. Louis-based agency go back to the mid-1960s, flew in from Chicago the day of the demonstration. With his typical good humor, he remarked, “fooling with this Wings of Hope stuff, it really opens your eyes.”

One whose eyes had been opened ten years ago, pilot Ed Schertz, was also on hand. Schertz flew in Paraguay for two years and in Peru for more than seven. His respect for the people with whom he worked is evident.

“The people some refer to as savages’ are the best cultured. They have a civilization of their own – with very little crime. They are good, moral people.”

Schertz added that he has “learned a lot” during his years of service for Wings of Hope, flying without meteorological aids or communication facilities and relying on himself as his own airplane mechanic, as is the case with most of Wings of Hope’s pilots.

Says Johnsen, “Everybody goes with a ‘can-do’ spirit. It’s a good thing you don’t know what you might be in for because you might be appalled by the enormity of the task.”

To offer support to this task, contact Wings of Hope, Inc., 2319 Hampton Ave., St. Louis, Mo., 63139, or call Wings of Hope at 647-5631.

CAPTIONS:

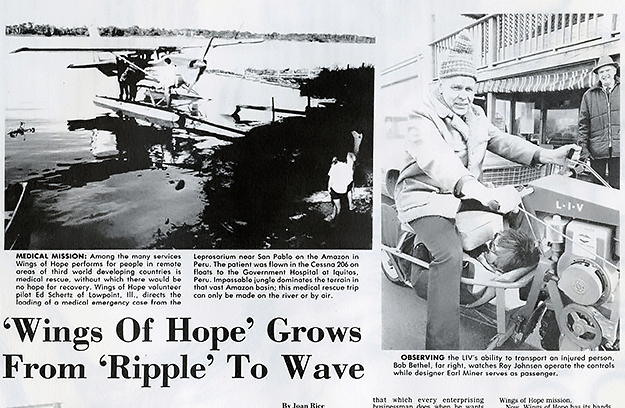

#1: Medical Mission: Among the many services Wings of Hope performs for people in remote areas of third world developing countries is medical rescue, without which there would be no hope for recovery. Wings of Hope volunteer pilot Ed Schertz of Lowpoint, Ill., directs the loading of a medical emergency case from the Leprosarium near San Pablo on the Amazon in Peru. The patient was flown in the Cessna 206 on floats to the Government Hospital at Iquitos, Peru. Impassable jungle dominates the terrain in that vast Amazon basin; this medical rescue trip can only be made on the river or by air.

#2: Observing the LIV’s ability to transport an injured person, Bob Bethel, far right, watches Roy Johnsen operate the controls while designer Earl Miner serves as passenger.

#3: Learning about LIV, the acronym for Earl Miner’s third world transportation machine, Little International Vehicle, are Wings of Hope people. Back row, from left, are Clancy Hess, a pilot; Bob Bethel, electronics advisor; Ed Schertz, a pilot and Roy Johnsen, operations director. Hess’ daughter Kathy sits in the front next to Miner.

#4: Images of dear friends and relatives line the cluttered desk of Wings of Hope Executive Director William D. Edwards as he discusses the organization’s efforts in his Hampton office. Edwards, a resident of Clayton, has coordinated the Wings of Hope operations since the firm was established in 1962. He says Wings of Hope is a non-sectarian, nonprofit, non-political humanitarian “aviation” agency, the only one of its kind in the world today.