Date: July-August 1974

By: Charles W. Ryan

Magazine: National Aeronautics

Page: 34-37

With planes and parachutes, the Wings of Hope a charity organization – provides emergency medical assistance, help, and food, from the jungles of Southeast Asia and the Amazon to the deserts of Africa.

Mayan to Spanish to English … a cry for help, relayed by two-way radio from village to village in a remote part of mountainous Guatemala. A 12-year-old Indian boy has fallen from a tree, suffering a compound fracture of the femur. The jagged bone ends protrude through the skin of his thigh, and the people of his village know nothing of first aid; how to splint the leg; how to guard against infection. And the nearest hospital is four days’ hike through rugged jungle. In that time the combined effects of shock and infection don’t leave much room for hope.

Twenty minutes after the message is received at Wings of Hope headquarters, the Cessna 206 (with a Robertson STOL conversion and a floor-mounted stretcher) is airborne.

Forty minutes later, Sink Manning, 32, a pilot/mechanic from St. Louis, Missouri, sights the 1200-foot air strip hacked out of the jungle. He makes a low pass to check the wind, always tricky in this mountainous region, and to look for animals or debris on the runway. He comes in for a landing – made difficult by the 7,000-foot elevation

and hot, humid climate – while Michael Stewart, 23, a pilot/medic from Winslow, Arizona, checks his gear and mentally reviews his medical procedures.

Manning and Stewart are on the ground before the injured boy arrives. It takes an hour to bring him along the primitive burro trail from his village.

Minutes after the boy arrives at the air strip, he is on his way to the airport at Guatemala City, where an ambulance is waiting to take him to the hospital. (Without Wings of Hope, four agonizing and dangerous days would have been spent on the trek to the nearest town where he could be taken to a hospital by automobile. He might not have made it.)

Even without his injury, the air trip to Guatemala City would have been a trial for the boy. He was alone with two strangers and flying in an airplane for the first time in his life. And there was no room in the plane for anyone of his tribe to go with him. But word of the Norteamericanos who fly in to bring help in medical emergencies has spread among the Indians in that remote part of Guatemala, and the boy knew he was with friends.

The Wings of Hope headquarters for Guatemala and all of Central America are located at the town of Santa Cruz de! Quiche, 40 miles north of Guatemala City and 7,000 feet above sea level. Mr. Sink Manning, Director of Operations and the pilot mentioned in the case history above, has provided two-way radios to all the villages in the area he serves. Thus, help can be on the way almost immediately when a medical emergency occurs.

Wings of Hope, Inc. is an aviation-oriented charity whose mission is to assist in medical emergencies among people in areas remote from even rudimentary medical facilities. Founded eight years ago and based in St. Louis, Missouri, the organization now has aircraft and volunteer workers operating in many parts of the world, providing desperately needed medical help and food from the jungles of Southeast Asia and the Amazon to the deserts of Africa.

According to Mr. George E. Haddaway, Chairman of the Board, this completely non-denominational aviation missionary group is unique because more than 95 per cent of all donated funds have gone entirely to supplying airplanes and the support services that go with them. And all funds are donated. Wings of Hope, unlike some flying doctor services such as those in Australia, receives no government funds, and no government involvement has ever been sought.

The organization offers its services to any legitimate missionary enterprise regardless of affiliation. For example, Wings of Hope has one airplane, sponsored by a Canadian religious group, that assists Wycliffe Associates (including Jungle Aviation and Radio Service), the Seventh Day Adventists, and Roman Catholic medical missions, all on the same route circuit. The youngest Wings of Hope pilot is a Mennonite. Many Wings of Hope volunteers work for the organization not because of any formal religious affiliation but because they have a deeply personal interest in serving humanity.

Manning and Stewart, of the Guatemala headquarters for Central America, are developing two new approaches in support of the actual flight operations. The first is the use of native doctors, in the remote villages served by Wings of Hope, to teach the inhabitants of those villages basic first aid and techniques to prevent infection.

The second approach is unique. There are some locations in their area where the terrain is too rugged for air strips. To cope with this problem, parachuting is being introduced to serve such isolated people.

Mr. Steve Snyder, of Paraflite, Inc., Mr. Ted Strong, of Strong Enterprises, Inc., and Mr. Harold McElfish Parachute Service, have already donated parachutes and equipment for the Guatemala parachuting operation. Mr. Perry Stevens, of Stevens Para-Loft, has trained Michael Stewart, a sport parachutist and a member of the United States Parachute Association, for his FAA rigger’s license, so he can repair and maintain the parachute equipment and inspect and repack the reserve parachutes.

There is precedent for the use of parachutists in remote areas. Members of the crack Peruvian paratrooper team, the “Singhis,” were dropped at Cutivireni, in the jungles of southern Peru, to help the villagers and missionaries clear the giant hardwood trees from the site of a proposed air strip. Then a small Ford tractor was flown in, piece by piece, and reassembled at Cutivireni for use in pulling out the stumps.

No one can hire or charter Wings of Hope aircraft. Every service is completely free. During the past eight years of operating aircraft over all sorts of terrain and under every possible type of climatic conditions, the organization has experienced about every conceivable flight, mechanical, and communications problem found anywhere. And the key to success has been the ability to work out the solutions and apply them to operations in all parts of the world: in the jungles of the Amazon, in the Turkana desert of Africa, in Biafra, in New Guinea, in Southeast Asia – wherever people need help and Wings of Hope can establish an operation.

Quietly, without fanfare, Wings of Hope is spreading the kind of good news about America that is rarely found in the newspapers nowadays. The mission of the organization is not political, but the fringe benefits in good will are enormous.

Deep in the Amazon, a Cessna 206 on floats carries a native, just bitten by a deadly bushmaster snake, to a well-staffed hospital while the same trip by boat would take more than two days.

An American-made light twin, taking off in the mountain vastness of New Guinea 10,000 feet above sea level, flies a woman dying in childbirth to a seashore village hospital in 20 minutes and saves her life. (The only other means of transportation is by mule or by a Land Rover bouncing over mountain trails for 18 hours.)

According to Wings of Hope President Joe Fabick, a St. Louis businessman, pilot, and aircraft owner, the ideal situation for the organization in future years would be to serve as a provider of aircraft and related equipment to self-sufficient sponsoring organizations, to enlist and train personnel, to serve as a logistical supply source or purchasing agent, and to function as a clearing house for all missionary aircraft operations throughout the world.

An important step in this direction has already been taken. One of the finest schools of aviation technology in the nation is at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois. The head of the aviation technology department is Mr. E.A. (Tony) DaRosa, who serves as technical advisor to Wings of Hope. Plans are being worked out for bush pilot training and new maintenance and repair operations designed specifically for bush flying. DaRosa has over 20 years’ experience in jungle flying through flight instruction of missionaries and providing of technical assistance and supply services for operations in New Guinea.

The missionary aviation training program is unique in that the student receives one and one-half to two years of comprehensive flight instruction as well as training in aircraft mechanics. The graduate also receives an FAA commercial pilot license and a mechanic license for the airframe and powerplant.

This in-depth training has helped the flying missionary to make better judgments about the airworthiness of his aircraft, to establish protective and corrective measures against adverse climatic environments, to insure structural integrity when operating from inadequate fields, and to perform repair and maintenance on the aircraft.

In some locations a fair amount of such maintenance is being performed by the natives under the supervision of the flying missionaries. This arrangement gives the natives a feeling of participation and usefulness and provides some relief for the overworked missionaries, freeing them for other tasks.

The heart of any successful bush flying operation is in developing the technical expertise that guarantees safe and effective use of aircraft. Missionary flying history is filled with cases of tragedy and failure where this fact of life was not recognized.

Why has the United States accounted for the bulk of humanitarian use of aircraft throughout the world?

Not only is it the wealthiest nation on earth, but it has been most generous in providing money, manpower, and equipment whenever disaster strikes.

America leads the world in the number and variety of civil aircraft. American aircraft, engines, and avionics have become standard in the aviation world. In recent years more than 25 per cent of U.S. and Canadian civil aircraft production has been for export. Perhaps 90 percent of all aircraft going into countries that produce no aircraft are out of American factories.

American missionary flight operations such as Wings of Hope have had a tremendous influence on the ready acceptance of American equipment abroad. U.S. aircraft and equipment have become so tied to developing countries that it is difficult if not impossible for products from other nations to penetrate the market place. This is especially true of U.S. aircraft engines, accessories, and avionics where non-American airframes are involved.

Less measurable than the economic influence of American missionary flying, but perhaps more important, is the good will created by these operations. This can be summed up by the statement of a missionary pilot in East Africa after he had rushed a desert chief’s baby to a hospital in Nairobi, Kenya, where its life was saved by emergency surgery.

The pilot said, “Out here on the desert you don’t have to do any propagandizing about the United States. You just do your job of looking after these poor folks when the emergencies arise. They know where the assistance is coming from. And that’s why a lot of communist infiltrators who poured into these newly independent, emerging countries in the 1960’s found such barren ground for their insidious propaganda against the free world. They came, they lost, they left.”

With the wide range of American utility aircraft to choose from, it is not too difficult to find the right airplane for any specific mission. It is not so easy to find the special kind of manpower required for the missionary aviation field. (One Wings of Hope pilot not only does all the routine maintenance on the aircraft and engine but also has become adept at pulling teeth because painful, rotten teeth are a major health problem of the natives in the area he serves.) Those who qualify, however, find their tours of duty with Wings of Hope to be a richly rewarding experience.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Pilots interested in· this interesting and humanitarian missionary service can contact Wings of Hope at 2319 Hampton Avenue, St. Louis, Missouri 63139; telephone (314) 647-5631.

CAPTIONS:

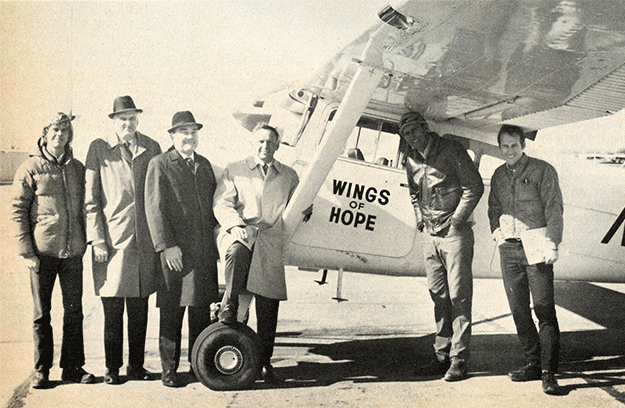

#1: A brand new Cessna 185 ready for delivery to Guatemala. From left: pilot/medic Michael Stewart, electronic expert Robert Bethel, Wings of Hope exec. W. D. Edwards, Wings of Hope President Joseph G. Fabick, pilot “Sink” Manning, pilot Bill Brand.

#2: One lone airplane over some of the most rugged terrain in the world, on a mission of mercy.

#3: Deep in the jungles of Peru , a missionary of Wings of Hope dispenses food, medical care and understanding to some primitive Peruvian Indians.

#4: A group of dedicated North Americans has brought hundreds of backwoods South Americans face-to-face with modern life: airplanes, cameras and medicine.

#5: Peruvian Army paratroopers drop into a remote jungle area near Cutivireni to help villagers hack out an airstrip from the dense, inaccessible growth.

#6: One very sick Peruvian boy gets a second chance. Field Director Guy Gervais helps load him for a flight from an Amazon settlement to a hospital in Iquitos.