Date: June 18, 1979

Location: Chicago, IL

By: Kay Rutherford

Newspaper: Chicago Sun-Times

Page: 12

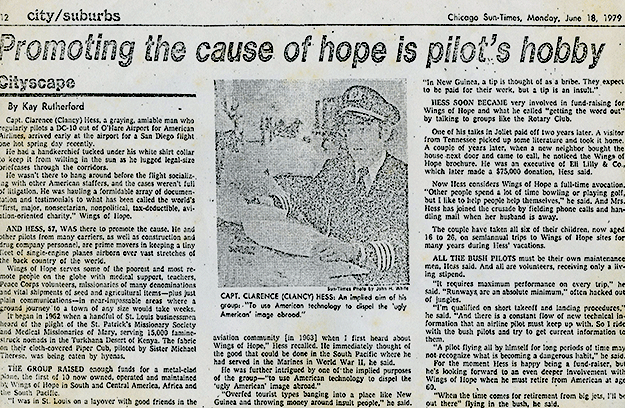

Capt. Clarence (Clancy) Hess, a graying, amiable man who regularly pilots a DC-10 out of O’Hare Airport for American Airlines, arrived early at the airport for a San Diego flight one hot spring day recently.

He had a handkerchief tucked under his white shirt collar to keep it from wilting in the sun as he lugged legal-size briefcases through the corridors.

He wasn’t there to hang around before the flight socializing with other American staffers, and the cases weren’t full of litigation. He was hauling a formidable array of documentation and testimonials to what has been called the world’s “first, major, nonsectarian, nonpolitical, tax-deductible, aviation-oriented charity,” Wings of Hope.

And Hess, 57, was there Lo promote the cause. He and other pilots from many carriers, as well as construction and drug company personnel, are prime movers in keeping a tiny fleet of single-engine planes airborn over vast stretches of the back country of the world.

Wings of Hope serves some of the poorest and most remote people on the globe with medical support, teachers, Peace Corps volunteers, missionaries of many denominations and vital shipments of seed and agricultural items – plus just plain communications – in near-impassable areas where a ground journey to a town of any size would take weeks.

It began in 1962 when a handful of St. Louis businessmen heard of the plight of the St. Patrick’s Missionary Society and Medical Missionaries of Mary, serving 15,000 famine-struck nomads in the Turkhana Desert of Kenya. The fabric on their cloth-covered Piper Cub, piloted by Sister Michael Therese, was being eaten by hyenas.

The group raised enough funds for a metal-clad plane, the first of 10 now owned, operated and maintained by Wings of Hope in South and Central America, Africa and the South Pacific.

“I was in St. Louis on a layover with good friends in the aviation community [in 1963] when I first heard about Wings of Hope,” Hess recalled. He immediately thought of the good that could be done in the South Pacific where he had served in the Marines in World War II, he said.

He was further intrigued by one of the implied purposes of the group – “to use American technology to dispel the ‘ugly American’ image abroad.”

“Overfed tourist types banging into a place like New Guinea and throwing money around insult people,” he said. “In New Guinea, a tip is thought of as a bribe. They expect to be paid for their work, but a tip is an insult.”

Hess soon became very involved in fund-raising for Wings of Hope and what he called “getting the word out” by talking to groups like the Rotary Club.

One of his talks in Joliet paid off two years later. A visitor from Tennessee picked up some literature and took it home. A couple of years later, when a new neighbor bought the house next door and came to call, he noticed the Wings of Hope brochure. He was an executive of Eli Lilly & Co., which later made a $75,000 donation, Hess said.

Now Hess considers Wings of Hope a full-time avocation. “Other people spend a lot of time bowling or playing golf, but I like to help people help themselves,” he said. And Mrs. Hess has joined the crusade by fielding phone calls and handling mail when her husband is away.

The couple have taken all six of their children, now aged 16 to 20, on semiannual trips to Wings of Hope sites for many years during Hess’ vacations.

All the bush pilots must be their own maintenance men, Hess said. And all are volunteers, receiving only a living stipend.

“It requires maximum performance on every trip,” he said. “Runways, are an absolute minimum,” often Hacked out of jungles.

“I’m qualified on short takeoff and landing procedures,” he said. “And there is a constant flow of new technical information that an airline pilot must keep up with. So I ride with the bush pilots and try to get current information to them.

“A pilot flying all by himself for long periods of time may not recognize what is becoming a dangerous habit,” he said.

For the moment Hess is happy being a fund-raiser, but he’s looking forward to an even deeper involvement with Wings of Hope when he must retire from American at age 60.

“When the time comes for retirement from big jets, I’ll be out there” flying in the bush, he said.