Date: April 1966

By: George Barmann

Magazine: Extension

Page: N/A

Opening Letter from Mike Stimac

Dear UMATT Friend,

We are pleased to be able to send you this reprint of the April 1966 EXTENSION article on UMATT. We believe George Barmann does an outstanding job in gathering together the amazing diversity of “happenings” that have led from the early Turkana desert project to today’s exciting vision of UMATT INTERNATIONAL.

The pace of UMATT’s growth can be indicated by a few of the things that have happened in the two short months that have transpired since this article was first prepared. Another aircraft is on its way to join the UMATT fleet. It will service the area around Malawi, and be flown by young lay pilot Bill St. Andre, who has just completed extensive training in Dayton. Just added to the facilities at Dayton are a donated advanced electronic instrument flight trainer and multi-engine training. Still another aircraft will be on its way to Mangu at the end of the summer to bolster the vital African air education program managed in the schools there by UMATT. The fund for the UMATT Ethiopian air ambulance is growing, and we hope this project will reach reality this fall.

The press of this expansion, and the accelerated pulse that can be sensed throughout UMATT, make it crystal clear how much we owe to you, our supporters, for the strength found in the mystical life-thread that is UMATT. Make no mistake about it, your continued interest, contributions, and spreading of the work are absolutely essential to UMATT’s future. Take every pride that you can in UMATT’s accomplishments; they are in the truest sense, your accomplishments.

Sincerely,

Dr. Thomas A. Dwyer

UMATT Assoc. Director

God’s Bush Pilots in Africa

A new airline, inspired by Vatican II, is un1t1ng missionaries of all faiths in the most inaccessible sections of East Africa

Darkness had fallen over the lonely expanses of the Turkana Desert as the new Cessna Super Skywagon began to ease itself out of the sky.

On the ground, at the remote Catholic mission outpost of Lorogumo in northwestern Kenya, jubilant natives saw the plane’s beacon in the night. A barefoot runner with a blazing torch dashed through the darkness and suddenly a long series of little piles of kerosene-soaked thorn bushes burst into crackling flames. It was a welcome greeting for the pilot, Brother Michael Stimac of the Society of Mary, who had been watching for the lights of the mission station. Softly he set his plane and its cargo of essential supplies down on the fire-brightened runway.

Brother Mike’s visit to Lorogumo was routine. The “Lorogumo Express” is a regular flight on the Marianist Brother’s schedule. He stops there each week, dropping off an often critical cargo including water, bread, milk, meat, vegetables, blood plasma, vaccines and medicines.

The next day’s flight might take this missionary pilot into any one of half a dozen nations of East Africa, bringing the critically ill to hospitals, surveying desert terrain for possible water hole sites, or transporting Catholic and Protestant missionaries in a few hours over distances that otherwise would require days and even weeks of tedious and often dangerous travel.

Brother Mike Stimac is at once a symbol and the central figure in one of the most unusual organizations and movements of our time – UMATT, United Missionary Air Training and Transport. Directed by the Society of Mary at Nairobi, Kenya, and Dayton, Ohio, UMATT is dedicated to wiping out through personal service not only the barriers of race, but also the isolation of Catholics and Protestants from one another in the mission fields.

That isolation has been more than geographical. Yet, UMATT proposes to span the distances of geography and of history as well. In a move without precedent, UMATT is establishing a transportation network linking missionaries of all faiths in the most inaccessible sections of East Africa as partners in a war against famine, disease and destitution. In its operations, the movement reflects the philosophy and spirit of Vatican II, especially by implementing the Decree on Mission Activity of the Church which calls for collaboration with all men in improving social and economic life in developing nations.

UMATT, little more than a year old, is already a legend in Africa. The Africans see it as part of the answer to their rising expectations; the missionaries regard it as essential to their future effectiveness; bishops call for its expansion; and Pope Paul himself has given it his blessing.

At the University of Dayton, the Society of Mary is stepping up its professional flight-training program under the leadership of UMATT’s acting director, Brother Tom Dwyer.

At Mangu Boys’ School in Kenya, Brother Paul Koller is intensifying the Marianist-conducted air orientation program for African youths. Plans are being studied to put five UMATT planes in East African skies.

A dramatic breakthrough that would extend the program to Latin America and Australia is being contemplated. The vision of the Marianists includes a 5O-plane woridwide mission air force.

Desert famine sparked the airline. How has Brother Mike’s shiny red and white Skywagon stirred the hopes for the future in so short a time? The answer begins to unfold with the story of almost incredible famine and misery in the Turkana Desert several years ago.

Until late in 1961 , the desert was a politically “closed area.” Missionaries were not admitted for any purpose.

Even had they been granted entry, they would have faced an almost impossible task. The hundreds of thousands of desert people are nomads, who for uncounted years have been on the move with their goats, donkeys, camels and cattle in search of vegetation and water. With their home as wide as the desert, they live on the blood and milk of their livestock and clothe themselves in animal skins.

Failure of the 1961 “short rains” in the desert and a plague of army worms caused widespread famine and disease. The United States sent emergency food. Famine camps were opened and mission relief workers welcomed at last.

Bishop Joseph B. Houlihan, of Eldoret, Kenya, and a member of the St. Patrick’s Missionary Society, sent two priests into the desert. They found thousands of Turkana tribesmen dying and the roaming people sunk in grim despair. Vultures circled above clusters of the starving, while wild hyenas lurked nearby awaiting their chance for human prey.

By bush “telegraph” the nomads learned about the famine camps. Their plight was gradually eased as truckloads of U.S. food began to arrive after a long safari from the south over the roadless desert. Bishop Houlihan desperately appealed to Mother Mary Martin of the Medical Sisters of Mary in Ireland to send some medical Sisters.

Within a short time, three nuns arrived, the first white women ever to live in the Turkana Desert. Their convent was a tin shack in the scorching, swirling sand, amid mosquitoes, scorpions and snakes, 10 miles from water.

Supplies were essential. Automobiles in desert environment have a short life and limited utility. In one instance in Turkana two vehicles lasted but a few days. If the Sisters’ program of assistance to the tribesmen was to continue, an airplane seemed to be the only answer.

Back in the U.S., a priest in Mercer Island, Wash., heard the news of the hardships of the missionary nuns. The priest passed the word along to two airline pilots, Jerry Fay and Everett Donovan, who with the active interest of friends in Seattle, purchased a Piper Super-Cub plane for the Turkana Desert Sisters. This marked the birth of the flying missionary “Peace Corps.”

Sister Michael Therese, a Boston girl with a radiant smile and a wealth of energy and enthusiasm, became the “flying nun” of the desert, taking to the air on missions of mercy with only a little more than 40 hours of pilot time behind her. Her plane, now used for short desert flights, is integrated in the UMATT system.

Brother Mike, at this point, had already made aviation history in Kenya for his pioneer training work with African boys. In response to Bishop Houlihan’s appeal, the Marianist now entered activities in Turkana. Both Bishop Houlihan and Brother Mike were quick to see the miracles that might be wrought in the desolate desert vastness with the airplane.

Inspired by the bishop’s story of tragedy in the desert, a group of St. Louis men laid the foundation for the support of air mission service in Turkana. Following the bishop’s 1963 appeal, Joseph Fabick of the John Fabick Tractor Co. and William D. Edwards, a manufacturer’s representative, started the Turkana Desert Fund.

Meanwhile, in Dallas, an influential aviation publisher, George E. Haddaway of Flight Magazine, a director of the fund and a Protestant, spearheaded a drive to supply the medical missionaries with a workhorse plane.

“In all my 30 years of aviation publishing I’ve never found a greater need for an airplane,” Haddaway told private plane owners throughout the country. The publisher envisioned aid to the Sisters and to other missionaries as well.

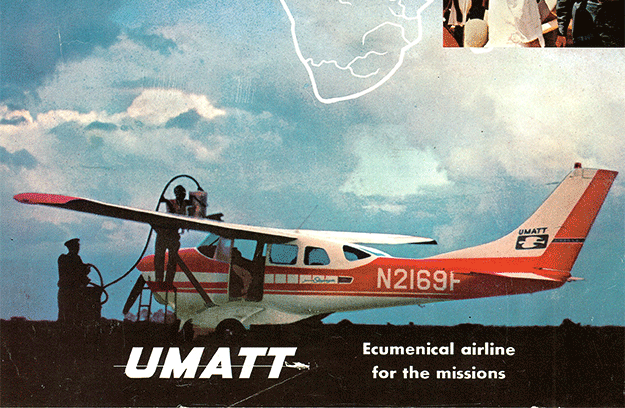

In April, 1965 – just a year ago – efforts reached fruition with the purchase of a $30,000 Skywagon. On that date, Brother Tom accepted the keys to the plane in behalf of UMATT and stressed that the air mission service would be nonsectarian in its operations.

“This is a service for men of good will in all faiths, working to help those whose lives and hopes will take on new dimensions because of the miracle of the airplane,” he said.

“It means fleetness to the doctors to heal the pained; it guarantees transport of bread and milk to feed the hungry; it means dignity to the youth of emerging nations, and it gives strength to the energies of the dedicated missionaries and Peace Corps workers in the field.”

The plane, “69 Foxtrot,” was to be based in Nairobi, Kenya’s capital city and busy gateway to the outside world. Brother Mike would be the first full-time pilot and administrator of the program in Africa.

The plane would link all remote missions of all faiths with one another, in addition to serving Turkana. At Turkana, where Sister Michael Therese had permanently established the value of mission aviation in the desert, the new plane would be especially welcome.

The Sister’s plane, wrote Bob Considine in a syndicated column, “has more patches than a bum’s pants.” The reason: Hyenas chew the fabric of the little Piper. The new plane would be all-metal and when placed in service the smaller craft then could become a “local” rather than an “express.”

In St. Louis, the big Cessna was prepared for its 9,000-mile trip to Nairobi. A world-famous pilot, Max Conrad, the “flying grandfather,” who has 10 children and 18 grandchildren, came from Arizona to pilot the plane to its destination.

On May 25, an interfaith dedication ceremony was held at Lambert-St. Louis Field. A specially designed UMATT flag was presented to Conrad for delivery to Brother Mike overseas. The flag, symbol of peace, showed a white dove on a blue background.

Conrad, accompanied by Marianist Brother Robert Thompson, piloted the plane to Dayton, UMATT’s home base, where another interfaith ceremony was held. Then Conrad headed for Africa, with Rome and the Vatican as one of his stopovers en route.

The Very Rev. Paul Hoffer, superior general of the Society of Mary, Conrad, and Brother Mike were granted a private audience with Pope Paul. He listened carefully to the UMATT plan, extended his blessing to those of all faiths who support it, and blessed the “dove of peace” flag.

At the end of its triumphal flight to its African home, “69 Foxtrot” was given a grand reception. On hand were members of the Protestant and Jewish communities, representatives of the Catholic bishops who then were in Rome for the Council, Bishop Houlihan in person, and civic, business and aviation leaders. After another interfaith, interracial homecoming in the bishop’s see town of Eldoret, the bishop and Brother Mike took off for the heart of the desert.

There they were greeted by Sister Michael Therese, the intrepid nun whose quiet service, played a vital role in the launching of UMATT. Her hands stained with the melting plastic from her Super Cub’s control stick, Sister delightedly examined the new plane.

The roomy plane immediately went to work, hauling cargo in and out of the desert. A medical airborne safari visited Turkana outposts with a nun-physician. Sick mothers, children needing transport for eye operations in Nairobi, and the elderly requiring special medical attention were typical passengers.

A government party was taken to Catholic and Protestant outposts to study health needs and housing. Another flight carried an official 180 miles over a dry river bed in search of water sources and irrigation opportunities. The two-hour flight saved a month of ground tracking to accomplish the same purpose. The aircraft performed beautifully despite the turbulence that buffeted the ship as it roared 50 feet

above the burning and eddying sand.

Still another typical desert assignment was a one-day sortie to complete plumbing work on facilities in an operating room of the medical Sisters. Without the flight, the job would have exhausted five days of overland travel and work, a prohibitive project.

More pleasant yet, Brother Mike eagerly accepted the task of bringing a desert worker at a Protestant mission, his wife and four children out of the bush to the capital city of Uganda where they were to begin their leave.

Into the plane went a mound of baggage, on top of which the entire family climbed. Instead of a dismal, uncomfortable ride of a full day over the scorching desert, the family made the trip in 90 minutes. Their clothing escaped the desert dust of a conventional tedious journey. The children, including one in a bassinet, completed the air trip without weariness.

In Nairobi, the Christian Council wanted to supply an African speaker for a convention three days journey toward Mozambique. Brother Mike delivered her in less than six hours.

On another occasion, five busy men climbed aboard in Nairobi for a Lutheran Synod meeting in Tanzania, arriving four hours later. On the return trip, “69 Foxtrot” dropped down to 50 feet 200 miles from Nairobi and a box of medicine was kicked out the door for a mission hospital. The hospital had radioed the Flying Doctors, who make use of UMATT schedules on every possible occasion.

Once, deep in Masaii territory, a radio nurse from the Flying Doctors got a message through to the plane that a priest had been shot and needed to be removed to Nairobi for deep surgery. The plane promptly headed for “restricted” territory and 90 minutes later the injured priest and a companion were in the aircraft.

Back in Nairobi, surgeons found that the bullet had narrowly missed the spinal cord and had perforated the intestinal tract. The damage was successfully repaired.

Supplemental fuel supplies for the UMATT plane now are maintained at numerous locations in East Africa.

Flying is not easy in East Africa. “Maps are a headache,” said Brother Mike. “They are incomplete in many ways and often one goes 150 miles between possible landmarks. You do a lot of intense staring at the horizon and must religiously watch the compass.

“One of the most useful instruments is the clock. When you run out of ETA (estimated time of arrival), you just don’t keep flying five minutes more out here. Find the strip or head for known ground. Many times the radio comes in handy. The pilot calls out the landmarks to the mission station and the station directs the plane home.”

A fascinating story. Pilot George Raymond, assistant UMATT African director in Nairobi, and his wife, Helen, both Protestants, are advancing the work of the mission air service at their headquarters in Nairobi.

The remarkable story of how they went to that part of the world, leaving behind a responsible post in an aircraft company and a comfortable California home, begins with a Christmas Eve flight in a helicopter. Raymond, with 1,500 hours of flying time, and his wife were en route to Bakersfield from Culver City when they were forced low by a fog bank.

The rotor blade failed and the copter plunged to the ground with a resounding crash.

“It ended up in a mess,” he said. “We had no business walking away from it, but we did.”

Their amazing escape from serious injury prompted them to reflect deeply on the meaning of their lives. They were certain they owed something for their good fortune and they sought repayment in service to the poor in the mission fields.

They wrote to UMATT and offered their services. Now, in Nairobi, they concede that they have never been busier or happier in their lives.

Raymond, a jolly personality with a facility for making friends easily, envisions UMATT as a world venture, stretching from the University of Dayton through Latin America, across the Atlantic through Africa, and then through India, Australia, into New Guinea and across the Pacific, forming vital “life lines” for Christian missionaries.

The immediate future, however, calls for expansion in Africa and solid support from friends of the missions everywhere. East African bishops have received a grant from the Propagation of the Faith to operate one of the UMATT planes.

The bulk of funds needed for growth, however, must come from industrial and secular philanthropic sources. A program has been initiated to secure a million and a quarter dollar endowment to support the UMATT fleet.

Private city and regional groups are forming in the U.S. to provide backing for individual planes. Following the example of the pioneering St. Louis group, supporting clubs are being activated in at least three major cities this spring.

At the University of Dayton, Brother Tom is overseeing the U.S. operations of UMATT, including training of pilots. The Society of Mary, who operate the school, has a core of 11 pilots.

In addition, he offers to all interested mission-bound personnel an aviation “ground school,” plus a few hours in the air, to enable non-pilots to handle the basic operation of a plane in an emergency. The latter program conceivably could save passengers in case the regular pilot became incapacitated through sudden illness in the air.

Part of the “back up force” for these UMATT pilots is another Society of Mary program called Front Line, a movement to supply lay missionaries. At the University of Dayton, Front Line, under the leadership of a Marianist priest, Father Philip Hoelle, conducts a mission training course throughout the school year.

Front Line also operates a settlement house in a Dayton poverty area where its members can engage actively in the apostolate to the poor. One Front Liner is Bill St. Andre, a graduate of Holy Cross college, who had flight training in the Navy. St. Andre works with Brother Tom in the UMATT headquarters at the university. He is scheduled to be the next UMATT pilot assigned to African duty.

In addition to Brother Mike, the pilot personnel in Africa includes Brother Joseph Fagan and Raymond at Nairobi, Brother Paul at Mangu and Sister Michael Therese in the Turkana Desert.

In Brother Tom’s headquarters in the basement of new and imposing Miriam Hall on the University of Dayton campus is a sign which reads: “The Grace L. Ferguson Airline and Storm Door Co.” This is the line “that goes to fields other airlines shun.” The Marianist “air force” makes jokes about the sign, but in a way it typifies the light-hearted optimism that permeates UMATT, a spirit determined to create from a modest beginning a movement with a worldwide impact.

UMATT’s pioneer effort to provide basic training in the principles of aviation is more than a Marianist recognition of the dignity and aspirations of the African. It is a practical means to assist in the development of Africa by developing African skills and talents. For it is, ultimately, the African who holds the key

to this Continent.

Brother Michael Stimac, S.M. sparkplug of UMATT

A diminutive fireball, 42-year old Brother Michael Stimac, the founder of UMATT, went to Africa in 1962, with a background of high school teaching in the United States and five years of experience in the Society of Mary’s mission efforts in Puerto Rico.

In fact, UMATT really got its start years ago when Brother Michael Stimac was teaching high school at St. Joseph’s in Cleveland. There, he began to expand the laboratory experience idea to involve young people in using the myriad principles of science illustrated by the airplane. Aerodynamics, structural engineering, electronics, navigation, mathematics – virtually every basic law of physics were all wrapped up in an appealing package that represented sound pedagogy at its finest. Just as important, it helped cement the bond between student and teacher so vital in the teaching apostolate.

The national reputation of St. Joseph’s “flying laboratory” led to Brother Mike’s assignment to the missions of East Africa. Here he again made a break with tradition, going on the assumption that the young Kenyans were as intelligent and sensitive as his students back in the States.

A Kenyan newspaper reported that Brother Mike’s efforts were the first step in providing the country with a supply of local-trained pilots. An Ethiopian daily, even more hopeful, said his program could result in “an inexhaustible source for African pilots.”

Brother Mike’s air program mushroomed, the vision of what aviation could mean to the people of Africa broadened, and the idea for UMATT was born.

The crew-cut Marianist religious is no talkative extrovert. He’s a man of quiet determination – a rare combination of idea man and doer. When be explained the aims of the East African venture to Cleveland business executive Dwight P. Joyce, a Unitarian, Joyce was immediately impressed by Brother’s “earnestness and dedication,” and raised $7,000 for UMATT. With this and similar help the airline literally got off the ground and into the air.

Brother Mike sees UMATT’s air mission service as a vital need for the future extension of Christianity in Africa.

Because of the vastness of the land there is a wide separation between centers of supply and administration.

Poor roads and circuitous routing waste a missioner’s precious time in an era when Christianity is in danger of being engulfed by the rising tide of paganism and Communism.

Missionaries are “trapped” in their isolation. Doctors and teachers are hampered by lack of outside contact for supplies and consultative facilities.

“The only solution is aviation,” says Brother Stimac. “It has now been amply demonstrated in Catholic African missions that the modern light business airplane is a complete and economical answer to the problems of efficient use of valuable manpower and of keeping pace with administrative demands.”

UMATT in action

The following example of what UMATT is capable of doing is condensed from a memo by George Raymond, director of UMATT, Nairobi, Kenya.

After clearing customs at the Haile Selassie Airport, we were directed to Princess Tsahai Hospital where R.H.J. and Catherine Hamlin, both physicians and surgeons specializing in gynecology, were waiting for us.

My ability as a writer is insufficient to describe what we saw upon reaching the hospital.

The women who have ruptured bladders arising from obstructed labours often walk a long way to reach the hospital traveling over mountains and nearly impassable country. When they arrive at the hospital they are often afraid to enter because of their urinary incontinence, but they are at once made welcome and are accommodated in a waiting house built by the Hamlin’s. His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I, the Emperor of Ethiopia, has repeatedly inspected this program and has supported it with personal donations of land and money. The Hamlins have a 10-bed ward devoted to the plastic reconstructive surgery of fistula patients and 30 other beds for general maternity and gynaecological work.

The dejection and misery of these women before operation defies all description.

Three weeks later the women leave the hospital with a new body, a new dress, carfare back to their village, and most of all a new outlook on life. They, are accepted back into the community, and many return to have their next child at the hospital.

It is seldom that any of us have the satisfaction of observing in such a short time -three weeks – the positive results of our interest in humanity. The shock is severe; the memory still very strongly with us.

The doctors hope eventually to eliminate this entire problem. That’s where we come in – flying these mothers to the hospital. To start off in a small way, we propose that one airplane cover an area of about two hundred miles along a main highway leading out of Addis Ababa to the Northwest. Police outposts are spaced along this highway. Their telephones would furnish communications.

The Hamlins estimate that most of the unfortunate mothers could be saved by merely two flights a week. The remainder of the flight time could be used to service Medical Missionaries of Mary Hospitals and other requests.

We strongly recommend serious consideration to the Hamlin’s request as well as the support of the Nairobi Unit, to all of you at home.

CAPTION:

#1: Brother Michael Stimac, founder of UMATT, plans a mercy flight in East Africa. He sees the airline as the most complete and economical answer to the problems involved in using missionary manpower efficiently and in supplying materials.

#2: A UMATT plane, donated by St. Louisans, is dedicated at an interfaith ceremony. Max Conrad, left, receives the flag from Turkana Desert Fund chairman Joe Fabick.

#3: A Kenya official, in pilot’s seat, welcomes UMATT – and Brother Mike and Max Conrad – to his country.

#4: Sister Michael Therese, the “flying nun” of the Turkana desert, takes to the air on a mission of mercy.

#5: Sister Campion assists in unloading vaccines, blood plasma, and other critical cargo for Kakuma hospital.

#6: This African youth demonstrates his grasp of aerodynamics and the basic mechanics of a plane, a first step in supplying his country with local-trained pilots.

#7: A Turkana tribal chief thanks Brother Michael and UMATT for helping his people.

#8: Pope Paul blesses UMATT flag as Bro. Mike, SM superior Fr. Hoffer and Conrad look on.

#9: Brother Tom Dwyer directs UMATT from the home front at the University of Dayton.

#10: Anglican Bishop Beecher of East Africa, left, greets Brother Paul Koller and Brother Mike.

#11: Someday UMATT airplanes may be looked up to in mission skies over Latin America, Australia and even New Guinea.