Date: January 1992

By: Thomas B. Haines

Magazine: AOPA Pilot

Page: N/A

Wings of Hope puts general aviation airplanes to work worldwide.

In impoverished areas of South and Central America, Africa, and Indonesia, and even in North America, people peer hopefully into the sky upon hearing the drone of an engine. When a Cessna 206 swoops over the trees and onto the tiny dirt or grass strip barely wider than a sidewalk, the people rush forward, knowing help has arrived. To these people, the Cessna and its volunteer crew can mean the difference between life and death. On board may be vaccines to prevent needless deaths, breeding stock to improve the local livestock, seeds for new crops, development agency personnel, or building materials to construct a school or hospital.

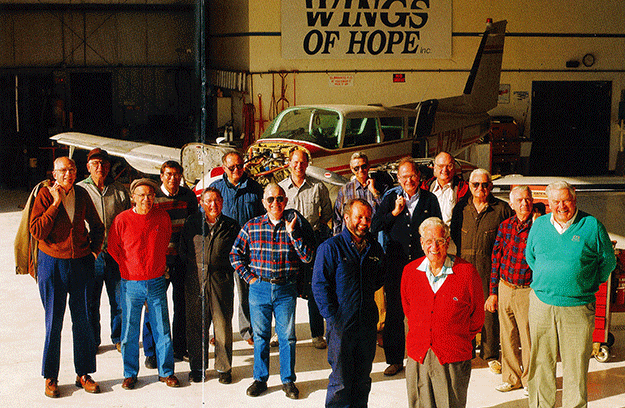

Providing the airplane is a St. Louis-based charitable organization called Wings of Hope. In a cluttered hangar at Spirit of St. Louis Airport, volunteers labor over well-worn 206s, turning them into literal wings of hope for those in need. Wings of Hope then donates the specially equipped airplanes to charitable organizations that have shown a need for the kind of help only an airplane can deliver.

At one time, corporations and individuals regularly donated the rugged 206s to Wings of Hope to be refurbished and readied for a new life in the bush. In fact, “in the good ol’ days” of the late 1970s and early 1980s when the airplanes were plentiful and tax breaks generous, the organization was sometimes donated brand-new airplanes. The 206 is the airplane of choice for relief work because of its large cargo doors and floor area, its weight-carrying capability, and its simple, rugged design, which makes for easier repairs. The high wings and tall gear permit better clearance in rough fields.

Many of the tax incentives are gone now, and because 206s are no longer in production, they are extremely valuable. As recently as 1987, people donated an average of two 206s a month to Wings of Hope. Since 1988, a total of three has been donated.

To stay alive, the 30-year-old organization takes whatever airplanes it can get in donation and refurbishes them using its skilled volunteer workers. Those airplanes unsuitable for field work are sold and the proceeds used to buy 206s.

Wings of Hope began in 1962 when a nun, who also happened to be a doctor and a pilot, had a problem with her missionary work in East Africa. She flew a Piper Cub around to the various missions, but the hyenas kept eating the dope and fabric on the airframe. She contacted some friends in the States and asked them to try to get her a metal airplane. Several St. Louis businessmen joined in the effort, and two years later, they were able to raise the funds to buy a 206 for her. Soon other relief agencies heard the story and began making similar requests, and the organization was born. Ninety-one airplanes later, Wings of Hope is still going. It has supplied aircraft for relief agencies around the world and in our own backyard. A priest uses a Cessna 337 to get around the southwest United States, where he serves as a missionary to American Indians. Two Wings of Hope aircraft are used for mission work in Canada. Though many of the relief organizations that operate its aircraft are church-affiliated, Wings of Hope bills itself as being “humanitarian, non-profit, non-sectarian, non-political, and tax-exempt.”

Wings of Hope usually puts heavy-duty gear and brakes on the aircraft it refurbishes. Depending on the intended mission, sometimes the aircraft are put on floats. STOL kits are added to improve short-field and slow-flight characteristics. Wings of Hope also equips all of its aircraft with front-seat shoulder harnesses, six-cylinder exhaust gas temperature probes, long-range fuel tanks, and a new set of Bendix/King avionics, often including a high-frequency radio.

Wings of Hope normally donates the aircraft to other carefully screened charities. The charities are responsible for maintaining and crewing the aircraft. The exception is in northern Belize, where Wings of Hope serves as a contractor to the Belize government. Two Wings of Hope aircraft and two pilots fly medical relief missions. The government reimburses the organization for its costs only. Wings of Hope pays the pilots $15 per day and provides transportation and housing. Most pilots volunteer to spend a few months at the task, and then the next volunteers are brought in.

Because it sees its pilots as ambassadors of the organization and of the United States, Wings of Hope carefully screens candidates. “They must be good solid citizens with good judgment because they make a lot of decisions,” explains Don Malvern, president of Wings of Hope. “We had to let one volunteer go because he couldn’t say ‘no.’ No matter what the circumstances, he would take on a mission, sometimes taking too great a risk with lives and aircraft.”

Besides good judgment, pilots must have a commercial certificate with instrument rating and about 1,500 hours total time. Pilots with airframe and powerplant mechanic certificates are preferred because sometimes the closest maintenance shop is in the next country. Those meeting the criteria must pass a flight test with a Wings of Hope check pilot. The flight test examines short-field, slow-flight, and crosswind skills and NDB and pilotage navigation abilities.

Though the pilots are the most visible members of the Wings of Hope team, Malvern is quick to credit all of the more than 100 volunteers who make up the organization. Wings of Hope has only one full-time employee, Edward J. Schertz, director of maintenance, and two part-time mechanics. Most of the volunteers are retired professionals from McDonnell Douglas Corporation. Malvern is a former president of McDonnell Aircraft Company, a division of MDC. He joined Wings of Hope as a volunteer in January 1989 and was named president three months later.

“I’ve been in aviation since childhood,” he says. “I’m really bitten by it. Wings is my thing, so the name of this organization really attracted me.”

Shortly after joining the organization, Malvern flew as a copilot on a medical mission in Belize. “We did a lot of good in just one day.” He delivered a convalescent patient from Belize City to an outlying area and picked up a sick girl and an Indian woman with a problem pregnancy for transport to a hospital.

“Our mission is so real: to use general aviation transportation in countries where the transportation system isn’t worth a darn.” According to Malvern, the infant mortality rate in the little town of Belize City has been cut drastically since Wings of Hope began serving the area. “It really hooks you,” he says of the work.

Hubert Looney got hooked on Wings of Hope after reading an article in a newspaper about the organization. He is an officer with the Missouri State Patrol, a fixed-wing and helicopter pilot, a mechanic, and a veteran of the U.S. Air Force and Army. “I can’t afford to donate money, but I can donate my time,” he explains. Looney spends his days off and vacations at the Wings of Hope hangar, helping with maintenance and doing odd jobs. “It’s very rewarding to know when an aircraft leaves here for a mission that you had a part in it.”

Lucy Fletcher agrees. “This is as close as you can come in a volunteer situation to seeing your work and effort being effective in helping people,” she says from behind a desk strewn with order sheets and parts receipts. She volunteers about one day a week to order and warehouse parts. “You couldn’t pay me to do this tedious work, but I’m glad to volunteer to do it.” She’s been a pilot since 1944 and once worked for the Civil Aeronautics Agency and then for a flight school. She recently retired from her position as a real estate agent. “This work has helped wean me from a full-time job. It allows me to have the satisfaction of accomplishing something.”

The volunteers at Wings of Hope are so enthusiastic about their work that they almost feel guilty about it. “I think maybe we’re a little selfish,” confides Robert Masters, who worked at McDonnell Aircraft along with Malvern. Masters commits one or two days a week to working on the aircraft, planning future projects, and tracking progress of each venture, much as he did at McDonnell, where one of his responsibilities was the F-18. “I’m not sure if we come out here for our own gratification or to help out the group.”

Everyone seems to have a specialty. Joe Meyer announces matter-of-factly that he’s been nominated fuel cell specialist. “Because my arms are so long. I’m the only one who can reach in far enough.” Meyer is retired from a product support position also at McDonnell. Of his experience at Wings of Hope, he explains, “It was a good chance to pay back some of my 40 years of aircraft knowledge.”

Likewise, John Bergtholdt is an A&P who has spent his life in aviation. He retired from Sabreliner Corp. and now drives 150 miles round-trip a couple of times a week to work at Wings of Hope. “Being in aircraft all my life, I felt I wouldn’t be content in anything else.”

All of the work is carefully documented to make it easier the next time. Cecil Sweeney, another McDonnell retiree, explains that he recently completed writing instructions for rebuilding fuel selector valves, overhauling hydraulic cylinders, and putting in auxiliary fuel tanks. “Now anyone can do it,” he beams.

Roy Robichaud, a pilot and manager of public relations and marketing for Wings of Hope and a retiree from Du Pont, shakes his head when he looks around at the volunteer talent in the hangar. “No company could afford to pay for this kind of talent, and they come out to help us for free; and no company ever had a more dedicated group.”

Robichaud and all the volunteers are quick to praise Schertz, the maintenance director. Schertz, who is a pilot and an A&P, and his wife, Irene, spent many years as missionaries in South and Central America. Perhaps he more than anyone at Wings of Hope is aware of the difference an airplane can make in countries with poor transportation facilities. He describes one flight he regularly made in South America. Supplies that would take weeks to get from one town to the next by boat on a winding tributary of the Amazon River could be delivered in 50 minutes in a 206.

One of Schertz’s biggest challenges is keeping everyone busy and keeping morale up when things are slow. When we visited the Wings of Hope hangar in late November, the group was repairing a Twin Comanche that was bound for mission work in southern Africa. The aircraft belongs to a minister. He was attempting a landing in Wichita where equipment was to be added for his flight to Africa when he skidded off the runway, damaging the right wing and landing gear. He called on the Wings of Hope crew for help. The minister is supplying the parts for the job, and Wings of Hope is proving the labor. Last fall, Wings of Hope completed a 206 and dispatched it to Canada to be fitted with fuel tanks for the journey to its new home in Zaire.

Where Wings of Hope’s main task once was simply readying donated aircraft for mission work, today it must concentrate on helping other relief organizations raise the funds to purchase aircraft. And where once it had a budget of about $1 million, today it gets by on about $100,000. “We’re in business to be broke and to stay broke,” Robichaud acknowledges. Nonetheless, Wings of Hope needs a steady revenue stream to keep the lights on and the deliveries on track. The organization regularly solicits foundations and corporations for cash donations. It also recently established a membership program for individuals. In some cases, other organizations have adopted Wings of Hope as their charity. A Rotary Club in Wyoming is providing money to buy an aircraft. Another group organized a golf tournament and raised $18,000 for Wings of Hope. A woman’s organization is hosting a fashion show that is expected to net Wings of Hope about $10,000, according to Robichaud.

He and others involved in fund raising also try to identify pilots who might be interested in donating their aircraft. One pilot has a Cessna 210 that will be given to Wings of Hope upon his death. Volunteers learned of an elderly man near St. Louis who owned a Cessna 150 but rarely flew it. They convinced him to donate it. Wings of Hope fixed it up and sold it. Another owner donated a seldom-used Beech Bonanza. Valuable aircraft sit idly on nearly every airport, notes Robichaud. “Most people don’t realize just how much good they can do.”

No one donation can change the world, he says, but each contributes a little toward sustaining an effort to improve the lives of the needy and toward keeping alive a brotherhood built on the wings of hope.

For more information, contact Wings of Hope, 1750 South Brentwood, Suite 352, St. Louis, Missouri 63144; telephone 800/4-HOPE-89 (800/446-7389).